Introduction

1.1 On 13 November 2024, the (then) Secretary of State for Transport commissioned ORR to undertake an independent review of train operators’ revenue protection practices.

1.2 Broadly speaking, the term ‘revenue protection’ relates to the policies, procedures, activities and other arrangements that may be put in place by a train operator or other industry party to:

- ensure passengers pay the correct fare for their journey;

- discourage or prevent individuals from evading the correct fare or carrying out related fraudulent activity; and/or

- detect and investigate suspected fare evasion and minimise or recover any losses arising.

1.3 The need for revenue protection reflects the fact that free-riding on the network is a significant issue for the rail industry, with hundreds of millions of pounds of revenue estimated to be lost each year.

1.4 As the railway is funded principally through fare revenue and public subsidy, fare evasion impacts both honest fare-paying passengers and taxpayers. This defrauded revenue cannot be put into lowering fares, improving services or reducing subsidy that can then be used to fund other parts of the public sector.

1.5 The Secretary of State asked ORR to assess and make recommendations on revenue protection in relation to two principal areas: train operators’ and ticket retailers’ consumer practices, including how they communicate ticket conditions; and train operators’ enforcement and broader consumer practices in this area, including the use of prosecutions.

1.6 This commission was a response to concerns from passengers and the media, among others, regarding how revenue protection practices have been operating. These arose following a number of cases where train operators appeared to have taken disproportionate action against some passengers for apparently unintentional or minor transgressions of fares and ticketing rules, or where prosecutions were undertaken incorrectly. These are discussed below.

1.7 ORR was asked to carry out this review because of its role as the independent regulator for the railway in Great Britain. Established by and accountable to Parliament, ORR is independent of government, the rail industry and passengers, but is guided by statutory duties – including its duty to protect the interests of users of railway services.

1.8 This review was commissioned under section 51 of the Railways Act 2005, which enables ORR to provide advice, information and assistance to national authorities (including the Secretary of State) on request.

Scope of the review and implications of rail reform

1.9 This review covers:

- all train operating companies (TOCs) operating regular scheduled services predominantly on the mainline network – including those operated on behalf of the Department for Transport (DfT), devolved governments and city regions. It does not cover London Underground or other metro systems, but does include London Overground and Elizabeth line services; and

- in terms of ticket retailers, it includes all the TOCs and third party ticket retailers (TPRs) licensed to sell tickets for the mainline railway. It also covers all available channels for purchasing tickets including ticket offices, ticket vending machines (TVMs) and those online.

The specific TOCs and TPRs within the scope of the review are listed in Annex C. The full terms of reference for the review are available on our website.

1.10 It is important to note that wider fares and ticketing reform is outside the scope of this review. The UK Government has already committed to reviewing this area, with the aim of simplifying the fares system and making other improvements to benefit passengers. This report therefore does not cover broader ticketing policy.

1.11 We have not had time within the constraints of this review (or indeed the data) to consider the full cost implications of our recommendations or to carry out cost benefit analysis. This would need to be considered separately. However, in some cases there may be existing or planned work by government or the rail industry that could take account of our recommendations in a way that minimises additional costs.

1.12 While our recommendations are relevant to the industry as it is now, we recognise that the creation of Great British Railways (GBR) will lead to significant structural changes. In particular, 14 TOCs currently running passenger services on behalf of DfT will enter public ownership under GBR. However, several mainline TOCs will remain outside of GBR, including open access TOCs and those operating on behalf of the Scottish and Welsh governments and devolved city regions.

1.13 The UK Government’s programme of rail reform will inevitably affect how the recommendations in this report are addressed, but it does not mean that the changes need to wait. We have highlighted some areas where improvements could be made quickly.

1.14 Also, under the UK Government’s public ownership programme, TOCs currently contracted by DfT will gradually move into DfT Operator Limited as their contracts expire. This may provide impetus for the industry to begin acting in a more coordinated way and lead to some of the medium and longer term actions that underpin our recommendations being addressed ahead of the creation of GBR.

1.15 The rest of this chapter provides further background to the review. Note that there are some terms used that may not be fully explained until later in this report. These are defined in the glossary in Annex A. There is also a timeline of events relating to the review in Annex B.

Factors leading to this review

Requirement to hold a valid ticket

1.16 By way of context, around 1.6 billion journeys were made on the mainline railway in 2023-24. For these, passengers bought around 450 million tickets through retail channels (tickets sold at ticket offices, on trains, at TVMs and online), with the remainder of journeys being made via ‘Pay As You Go’ options including Contactless bank cards and smartcards such as Oyster (source: ORR Data Portal (journeys) and Rail Delivery Group ticket sales data, 2023 to 2024).

1.17 All passengers are required to hold a valid ticket when travelling on the rail network. This obligation is set out in condition 6 of the National Rail Conditions of Travel (NRCoT). In general terms, those travelling without a valid ticket (or other authority) for their journey are at risk of being penalised or prosecuted, unless an exemption applies – such as there being no facilities for the passenger to purchase a valid ticket before boarding.

1.18 Where a passenger is found to be travelling without a valid ticket, this is termed a ‘ticket irregularity’. Some examples of ticket irregularities are set out in the box below.

1.19 As we set out in chapter 4, there are a range of responses that a TOC may take where there is a ticket irregularity, depending on the circumstances. It may involve no further action, one of several types of notice (such as a penalty fare) or potentially a prosecution leading to a conviction.

Examples of ticket irregularities

- An adult travelling using a child ticket.

- Travelling with a ticket at an invalid time (e.g. in the peak period but with an off-peak ticket, or using an ‘Advance’ ticket for a specific service on a different train from that permitted on the ticket).

- Being unable to present a railcard when such a railcard has been used to buy a discounted ticket for a journey or using it in breach of the terms and conditions.

- Not carrying a valid photocard where one is required (e.g. for a season ticket).

Controversy in the media regarding revenue protection practices

1.20 During 2024, there were a number of reports in the media about individuals found without a valid ticket who were penalised or prosecuted (or threatened with prosecution) in circumstances where they appeared to have made an innocent mistake, typically in relation to minor breaches of the terms and conditions (T&Cs). These include the following:

- Infringement of 16-25 Railcard terms: The 16-25 Railcard T&Cs include a restriction regarding travel on weekdays before 10am. Before 10am, it is only permissible to use a ticket with a 16-25 Railcard discount if the cost of the ticket is £12 or more (except during July and August or on public holidays, when this condition does not apply, or unless the ticket is an ‘Advance’ ticket). This restriction seems to be not well known and, in particular, its applicability to tickets labelled for use “Anytime” appears to have been a source of misunderstanding for passengers.

- As reported, in September 2023, a woman travelled to Wigan with an Anytime Day Return ticket bought with a 16-25 Railcard. The normal price of this ticket was £4.80, but with a railcard discount this would have been £3.20 (a saving of £1.60). However, she travelled before 10am and her ticket price was less than £12. Having been allowed through the gateline with her ticket at her departure station, her ticket was checked later onboard the train and she was told it was invalid.

She received a conviction via the fast-track ‘Single Justice Procedure’ (SJP) and received a fine of over £450. However, she denied receiving a summons regarding the prosecution and so did not have the opportunity to plead not guilty or provide mitigation in her case; the first she heard of the prosecution was on receiving a letter informing her that she had been convicted. - In early September 2024, a student faced prosecution for travelling before 10am with an ‘Anytime’ ticket bought with a 16-25 Railcard discount. On realising his mistake, the student offered to pay the difference in cost (£1.90), but this was declined and he was subsequently threatened with prosecution. This threat was later dropped after the case gained widespread public attention.

- As reported, in September 2023, a woman travelled to Wigan with an Anytime Day Return ticket bought with a 16-25 Railcard. The normal price of this ticket was £4.80, but with a railcard discount this would have been £3.20 (a saving of £1.60). However, she travelled before 10am and her ticket price was less than £12. Having been allowed through the gateline with her ticket at her departure station, her ticket was checked later onboard the train and she was told it was invalid.

- Boarding the ‘wrong’ train: Certain tickets are only valid on specific trains but there is scope for confusion about this – particularly during disruption. For example, in April 2024, a student was travelling back to university during a period of rail strike disruption. She had a ticket for a particular TOC’s service. Given the disruption to services, she asked station staff whether she could board the next train (which was that of a different TOC). She said they had advised her that in the circumstances she could board it. Later, on the train, she was informed by the ticket inspector that she had an invalid ticket, despite explaining what the station staff had said.

She was subsequently charged with the offence of not providing a valid ticket on request. She pleaded guilty by correspondence under the SJP but set out the mitigating circumstances when doing so. She was convicted and fined. - Confusion regarding when you can buy a ticket on board a train and when you cannot. For example, a 62 year old man who had previously bought tickets on board a particular service could not do so on one occasion as there was no conductor. After alighting from the train he said he went to buy a ticket from the ticket office but this was refused and instead he was issued with a penalty fare.

1.21 Such cases have contributed to a sense that TOCs are taking a disproportionate approach to tackling fare evasion, with some people being penalised for what seem to be innocent and minor breaches of the rules amid a complex system. That is – complicated ticket conditions, different approaches across the network and inconsistent approaches by rail staff.

1.22 However, there are challenges for TOCs in dealing with cases like these. We explore these below in paragraphs 1.39 to 1.41.

Use of the Single Justice Procedure and quashing of fare evasion convictions

1.23 Leaving aside the issue of whether some TOCs have been taking a disproportionate approach to enforcing revenue protection, there have also been concerns about how TOCs conduct and manage private prosecutions. In the summer of 2024 the Chief Magistrate quashed six fare evasion convictions that had been prosecuted by two TOCs. These test cases then led to just over 59,000 other passenger convictions being quashed. These passengers had been prosecuted by one of eight TOCs who had incorrectly used the SJP to prosecute offences under the Regulation of Railways Act 1889 (‘RoRA’) (due to a change in ownership, unlawful prosecutions were brought by nine legal entities, with the TOCs involved listed on the GOV.UK website).

1.24 The SJP is discussed further in chapter 5. In short, it is a procedure that allows adult individuals to plead guilty to minor, non-imprisonable, offences without going to court. The outcome is determined by one magistrate with a legal advisor, rather than two or three magistrates under the conventional ‘open court’ process. The cases referred to above were quashed because the 2016 Order permitting mainline train operators to use the SJP only permits its use for certain offences. These include those under railway byelaws but not under RoRA (byelaws are discussed further in paragraphs 1.59 to 1.60 below). Other offences, such as those under RoRA, have to be brought through conventional proceedings in open court.

1.25 It is important to note that these cases were quashed due to a procedural error by the TOCs. If they had sought to prosecute these cases using the railway byelaws or used the conventional open court process – it is likely that many (if not most) of the convictions – other things being equal – would have stood. This matter raises issues about the oversight of prosecution proceedings by TOCs and also the conduct of SJP prosecutions by the court.

1.26 However, there have been concerns about how the SJP is used more broadly within the criminal justice system, beyond its use by TOCs. These include whether private prosecutions are being brought using the SJP that are not in the public interest and whether the process provides for fairness. In November 2024, the UK Government committed to review the SJP and private prosecutions more generally. The Ministry of Justice has since consulted on proposals to improve oversight and regulation in this area and at the time of publication of this report is in the process of considering the responses it received.

Impact of fare evasion

1.27 While noting the apparent disproportionality involved in some of the cases discussed above, it is important to recognise the rail industry’s perspective on this. Revenue protection is largely a necessary response to the significant financial loss caused by people intentionally avoiding paying the correct fare.

1.28 An updated estimate from earlier this year (from the Rail Delivery Group (RDG), GBR Transition Team and DfT) indicates that fare evasion and ticket fraud accounts for at least £350 to 400 million of lost revenue each year. Anecdotally, some industry stakeholders have told us that they believe the actual level of fare evasion is somewhat higher.

1.29 Given the scale of fare evasion and the impact it has, it is right that there are sanctions in place to deter or punish those who deliberately evade their fare. Indeed, there are periodic reports in the media of individuals being successfully prosecuted for clear and egregious cases of fare evasion.

Consequences of a system that passengers perceive to be unfair

1.30 Where passengers are penalised or prosecuted for genuine mistakes, it is important to note the consequences of this both for them and the industry. The range of consequences those passengers may face could include:

- a penalty fare;

- claims by the TOC for recovery of the full undiscounted train fare and any related TOC investigation costs (and – if the passenger challenges this – potential County Court Judgements via the civil courts that affect their credit rating); and

- a conviction for criminal offences that may blight their reputation, career and financial prospects.

1.31 Above all, there may be a feeling of injustice, particularly if there was an intention to comply with ticketing rules and they believed that they were acting in a law abiding way. This is likely to undermine trust and confidence in the railway and may discourage those passengers from using it in future. It is also likely that they will discourage others from using it given their experience. That is a bad outcome all round – for them and for the rail industry.

Key challenges for the rail industry

Complexity of the system

1.32 The current fares and ticketing system is widely recognised as being overly complicated and confusing for passengers and explains why many passengers unintentionally end up travelling without a valid ticket.

1.33 As new developments have emerged (such as ticket apps and contactless tickets), the system has adapted incrementally over time to meet evolving passenger needs and expectations, with new features largely bolted on, adding to the complexity. This has been done with good intentions. At the same time, the increasing volume and complexity of rail products has created opportunities for exploitation by passengers who seek to under pay or avoid their fare. This is a tension that explains many of the issues highlighted in this report.

1.34 Some examples of complexity and areas for confusion in the current system include:

- the role of conductors or guards on some services. If a passenger boards at a station without ticket-buying facilities, they can buy a ticket from the conductor or guard. However, passengers who had the opportunity to buy before boarding are generally expected to have done so, and are at risk of being penalised if they do not. The presence of a conductor/guard therefore can lead people to think they can buy on board in all circumstances;

- a wide range of tickets (and prices) available for essentially the same journey. It is not always clear what the difference between the ticket options is and which is the best one for that passenger;

- a wide range of conditions that may or may not apply, or can vary depending on circumstances. For example, whether a journey can be broken mid-way, whether a railcard can be used, or when the off-peak or peak begins and ends (and it can vary by TOC, by station and by direction of travel);

- ticket names and terminology which are not intuitive or immediately obvious to a layperson (e.g. ‘Super Off-Peak’, ‘Advance’, or ‘Any permitted route’); and

- ‘split ticketing’ – the nature of the current system is such that it can be possible to buy separate single tickets for different stages of a journey that, in total, are cheaper than a single ticket covering the whole journey. This leads some passengers to legitimately seek out cheaper options when planning a trip. However, certain conditions may need to be met to avoid falling foul of the rules.

1.35 For balance, it is right to point out that, for all the disadvantages of complexity, the current system does provide an array of choice to suit different passengers – provided they know what they are buying.

1.36 It is also important to note that some of the complexity may have been entirely rational within the context in which it was introduced. A good example is the 16 25 Railcard minimum fare restriction discussed earlier. When this rule was introduced, all tickets were purchased from a ticket office. Rail staff would have applied this rule themselves when selling a ticket, depending on when a passenger wanted to travel. It was therefore much harder for a passenger to inadvertently make a mistake and travel with an invalid ticket.

1.37 However, in an era when the majority of tickets are bought online or via a ticket vending machine (TVM) without the advice of staff, there is a much greater risk of people making mistakes. And this is the problem more broadly with a complex system where more ticket options, alongside more complex ticket types, necessitates the provision of more information to allow the passenger to make an informed choice.

1.38 This can increase the time and cognitive burden on passengers when buying a ticket – particularly for those making a journey as a ‘one-off’. In this context, it is inevitable that some people will make innocent mistakes and end up travelling with an invalid ticket. This complexity also creates a tension with modern app-based online retail options. These platforms prefer a ‘quick and easy’ transaction model to aid sales, which does not readily facilitate communication of complex terms.

‘Grey areas’

1.39 The rail industry, in principle, will not want to knowingly penalise someone who has made an innocent mistake. However, there are a number of grey areas in which it can be difficult to determine whether a mistake has been made innocently or not. The complexity of the fares and ticketing system outlined above is just one source of these. But there will be some individuals who know about the grey areas and seek to exploit these to avoid or underpay a fare, with the intention of feigning innocence if caught. A few examples of these are:

- buying a cheaper ticket with a certain condition (e.g. a ticket for a specific train service) and boarding a train on which the ticket is not valid.

- forgetting or losing a ticket, or travelling with the wrong portion of a return ticket (for example, using an unsurrendered outward bound ticket for a return journey); and

- not tapping-in with a contactless bank card or smartcard rail ticket: a person may have thought they tapped-in (and not realised that the system had not registered their card) or innocently and absentmindedly forgot to do so.

1.40 In all these cases a person could have acted deliberately and it can be difficult for a ticket inspector to know definitively whether a person has acted innocently or not. The scope for people to make innocent mistakes or be inadvertently caught out raises the question of whether (and what) safeguards might be established to provide a level of protection for genuine mistakes.

1.41 But the industry has to be mindful that any change that makes the system more ‘reasonable’ for those who have made a genuine mistake or who are acting with good intentions may risk introducing a new vulnerability to be exploited by those that wish to evade their fare or commit a related fraud.

Risk factors for fare evasion

1.42 The nature of a train service and the network it serves has an important bearing on the vulnerability of a TOC to fare evasion, and accordingly on the level of challenge for them in seeking to mitigate this risk.

- The majority of stations are ‘open’ (that is, they do not have ticket gates). As such, it is easy at these locations for people to enter and exit the rail system without a ticket, unless manual ticket checks are being carried out.

- Where there are onboard ticket checks, it is not always practical to check everyone’s ticket – particularly for services where there are relatively short distances between station stops.

- Ticket gates help to reduce the scope for people to travel without any ticket. But installing these is expensive, and they must still be staffed.

- By contrast, some types of service are less vulnerable to fare evasion. For example, on services with long distances between stops and where tickets are generally always checked (such as sleeper and some long distance services).

Different types of fare evader and ticket fraud

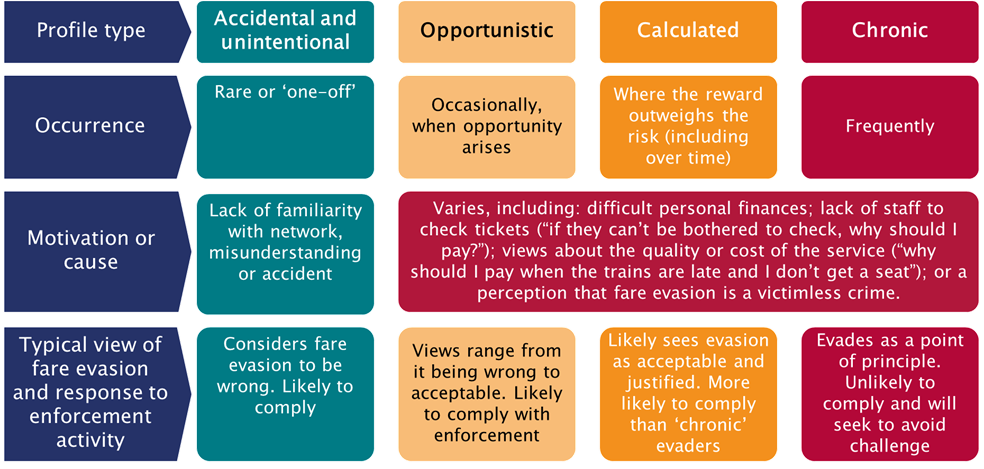

1.43 A further challenge for TOCs is that there is no single type of fare evader, which means there is unlikely to be a simple strategy for a TOC to adopt to address evasion. However, understanding the profiles of typical fare evaders can help to inform a more effective revenue protection approach. Some organisations have established categories of fare evader to help inform their approach (for example, Transport for London (TfL) in its revenue protection strategy). Illuminas’s report for Transport Focus also profiled different types of fare evader and there are others.

1.44 While the characterisation of different evader profiles can vary, they are broadly similar. Figure 1.1 below sets out one version of this, building on the different approaches to this we have seen.

Figure 1.1 Profiles of different types of fare evasion

1.45 The industry also has to deal with a range of fraudulent activity that contributes to fare evasion, including the altering or counterfeiting of tickets. This ranges from an individual undertaking such activity themselves through to more systematic organised criminal activity that defrauds the railway.

The organisations involved in revenue protection

Train operators

1.46 Reflecting that revenue protection is an important commercial matter, since privatisation it has been for TOCs to each set their own revenue protection strategy and approach, within the broader legislative framework. This includes employing staff or agents to support this – such as ticket inspectors, conductors, gateline staff, and back-office teams to investigate and if necessary prosecute individuals for fare evasion.

1.47 For TOCs that are operated on behalf of government, their approach will be influenced by any obligations relating to revenue protection placed on them by their sponsoring government body. For example, those TOCs contracted by DfT generally have contractual requirements regarding:

- minimising or mitigating the impact of any factors that would lead to revenue being reduced (or increasing slower than forecast). This obligation is monitored via targets for reducing ticketless travel; and

- regular reporting on revenue protection activities to DfT.

1.48 Most TOCs have published their revenue protection policies on their websites, setting out what passengers can expect. This can include any relevant processes such as how to appeal against a penalty fare and the role of any third party agents.

1.49 How TOCs approach revenue protection is further explored in chapter 4.

Rail Delivery Group

1.50 Although responsibility for revenue protection matters in the rail industry lies with TOCs, RDG provides support for this. In particular, it coordinates changes to the NRCoT and operates the National Rail retail website which provides information for passengers about ticket types and railcards and passes customers on to TOC retail sites for ticket purchases. It also provides the underlying industry systems that generate most of the data for tickets (this is discussed further in chapter 3).

Government

1.51 Government (at UK and national devolved level) generally has two distinct roles in relation to fare evasion:

- creating or amending legislation regarding fare evasion and overseeing its effectiveness. This includes laws that provide for prosecution of those caught evading fares and also regulation relating to penalty fares (where these are used); and

- where TOCs are contracted to government or publicly owned, setting any objectives for addressing fare evasion (such as obligations to reduce ticketless travel as noted above) and monitoring the TOC’s performance – e.g. to ensure they are actively working to minimise revenue loss in an effective manner.

Third party contractors

1.52 Many TOCs have contracted third party companies to support their revenue protection approach. These are discussed further in chapter 4 but in summary these companies offer a range of services including:

- carrying out ticketless travel surveys for TOCs;

- the provision of agency staff to carry out customer facing activities on behalf of the TOC (including onboard and gateline ticket inspection);

- the investigation of potential cases of fare evasion and related communication with the passenger – including enforcement and potentially decisions to prosecute. This includes considering disputes and mitigations raised by passengers; and

- provision of specialist software used for revenue protection (e.g. electronic systems for logging passenger details where there is a ticket irregularity and subsequent document and case management for any subsequent action).

Penalty fare appeals bodies

1.53 TOCs that issue penalty fares are required to provide an independent appeal service for passengers to use. TOCs currently use one of two companies to deliver this service, ‘Appeals Service’ (a trading name of ITAL Group Limited) or Penalty Services Limited. The appeals process is discussed further in chapter 4. Some TOCs contract with the penalty fares appeals bodies to provide a form of appeals process for other unregulated notices that they issue (i.e. unpaid fare notices).

British Transport Police

1.54 The British Transport Police (BTP) has a role in supporting certain categories of revenue protection work. This may include supporting significant ticket checking operations and supporting staff dealing with difficult passengers (including where a person will not give their details). BTP also investigates rail fraud where it is of a particularly high value. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) (in England and Wales) or Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal (in Scotland) would act as the prosecutor in these cases. However, BTP has finite resources and it will continually prioritise its focus on what it regards as areas of the greatest potential threat, risk and harm across the range of its responsibilities.

Consumer bodies

Transport Focus and London TravelWatch

1.55 As the statutory representative bodies for passengers in Great Britain and the London area respectively, Transport Focus and London TravelWatch have an interest in how TOCs carry out revenue protection. Neither body has a formal role in relation to revenue protection. However, by arrangement with DfT, Transport Focus oversees appointments to the independent panel that determines the third and final stage of appeals in relation to penalty fares. TfL also consults London TravelWatch regarding the independent panel for its own penalty fare regime.

1.56 However, as a consumer advocate, Transport Focus has been campaigning for better protections for passengers who find that they have inadvertently infringed the ticketing rules. Its 2012 ‘Ticket to Ride’ and 2015 ‘Ticket to Ride – an update’ publications show that concern about this is longstanding.

1.57 More recently in January 2025, Transport Focus published a list of proposals for improving the passenger experience in relation to revenue protection. Alongside this list of proposals, it also published research (commissioned from Illuminas) on passenger attitudes to fare evasion and revenue protection. This involved interviews with different categories of passengers, including honest fare-paying passengers and fare evaders.

Rail Ombudsman

1.58 The Rail Ombudsman, which provides a free service to passengers to investigate unresolved complaints, does not generally have a role in relation to complaints about revenue protection. However, it can investigate complaints about the quality of an interaction between revenue protection staff and a passenger, such as when a penalty fare or other such notice is being issued. We commissioned the Rail Ombudsman to produce a report on the complaints it has considered in this area, which we discuss further in chapter 2.

The legislative framework dealing with fare evasion

1.59 The legislative framework for addressing fare evasion has developed over time. Parliament has previously determined that intentional fare evasion can be dealt with as a criminal matter, and this has been the position since the 19th century. Parliament has also provided for railway byelaws to be made covering issues such as fare evasion and ticketing. Byelaws need to be issued under the authority of a government minister, but do not require further parliamentary oversight.

1.60 The most relevant legislation for prosecuting fare evasion is as follows (other legislation is available but is used less often, such as the Fraud Act 2006, which may be used in England and Wales to prosecute particularly serious cases of fare evasion or related fraud):

- Regulation of Railways Act 1889 (RoRA): In summary, section 5 of this Act makes it an offence:

- for a passenger to not provide their name and address upon request where they are unable to provide a valid ticket (section 5(1));

- to travel without paying the fare with intent to avoid payment (section 5(3)(a));

- having paid the fare for a certain distance, to intentionally travel beyond that distance with the intention of avoiding paying the additional fare (section 5(3)(b)); or

- to give a false name and address (section 5(3)(c)).

It provides for fines of up to £1,000 or, for repeat offences under section 5(3), imprisonment of up to three months as an alternative to a fine.

- Railway byelaws:

- Among other things, these byelaws make it an offence to travel without a valid ticket or to fail to produce a ticket on request (unless one of the few permitted defences applies). These are ‘strict liability’ offences, where the intent of a person does not matter. That is, a successful conviction does not require proof of intent. So, an innocent mistake such as forgetting a ticket can potentially lead to prosecution and a fine of up to £1,000.

- The Railway Byelaws 2005 apply to the mainline railway in most of Great Britain, except in relation to services or stations operated: (1) by or on behalf of TfL; or (2) Merseyrail. Instead, these are covered by separate (but substantively the same) byelaws (for further information, see TfL byelaws and Merseyrail byelaws). Byelaws 18(1) and 18(2) are particularly relevant to fare evasion. Where we refer to ‘applicable byelaws’ in this report, we mean any of these three sets of byelaws relevant in a particular situation.

- Since April 2016, TOCs have been authorised to use the SJP to prosecute byelaw offences.

1.61 In addition, or as an alternative to prosecution, TOCs may seek to recover unpaid fares via civil legal action.

1.62 Since first legislating for them in 1989, Parliament has also provided for penalty fare regimes to be established on the mainline network, providing a way to discourage people from travelling without a valid ticket outside of the criminal law.

1.63 Penalty fares are discussed in chapter 4 later, but it is worth noting this area has evolved since the early 1990s, with an inconsistent approach across Great Britain. Not all TOCs use penalty fares, and of those that do, all are based in either England or Wales. The current regime is based on the Railways (Penalty Fares) Regulations 2018 (the ‘2018 Regulations’).

1.64 However, since then, further devolution to the Welsh Government has occurred. So, when the 2018 Regulations were amended in 2022 to increase the penalty fare level (via the Railways (Penalty Fares) (Amendment) Regulations 2022 (the ‘2022 Regulations’)), this change did not extend to certain services in Wales. This means a different penalty fare level applies for Transport for Wales services (except while these are in England).

1.65 Since responsibility was devolved to the Scottish Government for rail, it has not introduced regulations to permit penalty fares to be used on Scottish services.

1.66 TfL has a wholly separate penalty fare regime (applying to Elizabeth line and London Overground services, as well as other transport modes such as buses and the London Underground).

1.67 Overall, it is important to note that there is a range of legislation available, providing TOCs with choice around the legislative tools they can use when tackling fare evasion.

1.68 It is also relevant to note that the Equality Act 2010 will have a bearing on revenue protection practices. For example, all TOCs have a duty to make reasonable adjustments for disabled passengers and must ensure that they do not discriminate against anyone with a protected characteristic, including for example age or disability.

1.69 Section 149 of the Equality Act also creates a specific duty (“the Public Sector Equality Duty” or PSED) which applies to public sector organisations. This, among other things, requires them to have due regard to the need to:

- eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and other conduct prohibited under the Equality Act 2010;

- advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not; and

- foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not.

1.70 The PSED applies to those TOCs that are in public ownership. These include the TOCs controlled by Transport Scotland and Transport for Wales, and those owned by DfTO, as well as other bodies carrying out public functions.

1.71 As illustrated earlier, there are a significant number of parties involved (to varying extents) in revenue protection. At TOC level, there are: 14 TOCs operating services on behalf of DfT (either under contract or publicly owned under DfTO); two publicly-owned TOCs in Scotland and one in Wales; two TOCs contracted by TfL and one by the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority. There are also currently four open access TOCs. For the most part, they can each take their own approach to revenue protection.

1.72 Further, as noted above, the legislative landscape for revenue protection is not entirely consistent across Great Britain – particularly in relation to penalty fares. This reflects that over the last 20 years or so devolution has transferred some relevant responsibilities to the Scottish and Welsh Governments, and to the Mayor of London. In addition, Scotland has a different legal system to England and Wales, which has implications for how fare evasion prosecutions take place there. This is shown in the flowcharts in Annex E.

1.73 This makes the landscape for revenue protection complex for both industry and passengers, particularly in respect of services travelling across borders within Great Britain.