Introduction

3.1 This chapter focuses on the impact of ticket retailing and T&Cs on revenue protection, as recognised in the terms of reference for this review:

- retailing information – including passengers’ access to accurate and complete information, and whether this is clearly and effectively communicated during the sales process (including online, at TVMs and ticket offices); and

- ticketing terms and conditions – the clarity of ticketing T&Cs, including within the NRCoT, railcard T&Cs, and other ticketing conditions.

3.2 This chapter examines these matters in detail, exploring:

- whether ticket sales channels provide passengers with the information they require, both to make an informed ticket purchase that meets their needs and to understand how they can use the ticket they have purchased;

- whether the industry systems and data that underpin ticket retailing affect passengers’ access to material information regarding their ticket that is accurate, transparent, and provided in a timely way; and

- whether T&Cs or ticket validity restrictions are clear to passengers or whether the complexity of these: (1) affects the ability of the passenger to understand the validity of their ticket; or (2) provides potential opportunities for passengers to intentionally evade their fare.

3.3 As noted in chapter 1, travelling with an invalid ticket may arise because of either of the following at the ticket-buying stage of a passenger’s journey:

- unintentional: system errors, passenger confusion or an inadvertent mistake arising from the T&Cs or validity of their ticket or railcard; or

- intentional: passengers deliberately exploiting ticket types and T&Cs to evade fares on the railway.

3.4 However, before looking into these matters, it is important to note the broader landscape for the retail of rail tickets.

The ticket retailing landscape

3.5 Rail tickets are sold and purchased through different channels:

- in-person sales at station ticket offices;

- at stations through TVMs; and

- online through websites and apps, by TOCs and TPRs.

3.6 In this report, when we refer to ‘retailers’, we mean both TOCs as retailers and TPRs.

3.7 There are also several companies that support these retailing activities by providing the underlying software for the online retailing platforms used by TOCs and TPRs. These are often referred to as ‘white label’ providers, with TOCs and TPRs then customising the look of these platforms on their websites and apps.

3.8 RDG oversees the online retailing of rail tickets. It licenses ticket retailers on behalf of TOCs and accredits the ticket issuing systems (TIS) that TIS suppliers and retailers build to sell rail tickets to passengers through online platforms. This process of licensing and accreditation is designed to ensure that:

- passengers have access to accurate fare, reservation and timetable data; and

- data on ticket sales is accurately submitted to centralised industry systems used to calculate settlement values and distribute rail revenues between TOCs.

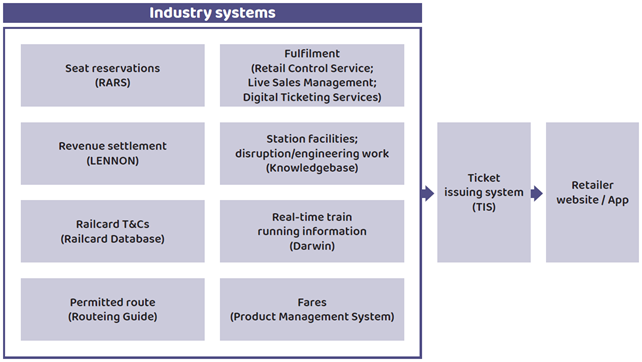

3.9 For a TIS to be accredited by RDG, the supplier must demonstrate that it can integrate with specified industry systems to ensure that the information provided to passengers reflects the data held on centralised industry systems. Retailers are not permitted to use information from other sources beyond those specified by RDG and could risk losing their accreditation if they do. The systems specified by RDG include those set out in Figure 3.1 below.

Figure 3.1 Key industry retail systems informing online ticket retail

Note: This diagram sets out the key systems TIS suppliers and retailers use to inform online sales channels and is not intended to be an exhaustive list. The systems referred to are defined in the glossary).

3.10 These industry retail systems have evolved over time to meet the growing demand for digital rail retail channels. Online sales channels have increased in popularity, with 77% of passengers now buying rail tickets through websites and apps at least some of the time according to DfT research (Source: Figure 4: Ticket purchasing behaviour and preferences among rail passengers, DfT. Research carried out in February and March 2023) from 2024.

3.11 To support online ticket sales, information that was originally intended for use by ticket office staff (who could interpret and explain it to passengers as necessary) has now been digitised and repurposed. It is now shared directly with passengers via online sales channels. However, this information was not designed to be presented to passengers without guidance or explanation.

Overview of ticket types

3.12 As noted in chapter 1, the current fares and ticketing structure in the rail industry is complex. However, within this structure there are several standard ticket types:

- Anytime:

- Single – Anytime Single tickets can be used within two days of the date shown on the ticket and up until 04:29 after the last day of validity. However, Anytime Day Single tickets are valid until 04:29 after the date shown.

- Return – Anytime Returns are generally valid for one calendar month on the ‘return’ portion. However, Anytime Day Return tickets are valid only for the date shown and until 04:29 the following morning.

- Off-Peak and Super Off-Peak:

- Single – a ticket that is only valid outside of peak-time. Off-Peak tickets are usually valid from 09:30 on weekdays in large cities and towns and from 09:00 elsewhere. The time restriction can be based on the time a train leaves or arrives at a city. Some cities also have evening peak time restrictions.

- Return – Off-Peak and Super Off-Peak Day tickets are only valid on the date shown on the ticket. Off-Peak and Super Off-Peak Returns are valid for one month from the date shown on the ticket.

- Advance – Advance tickets are only valid on the date and train specified and therefore offer no flexibility for time or date of travel. These tickets can be bought from 12 weeks before travel and up to 10 minutes before departure.

- Season – Season tickets allow unlimited travel for a particular journey and can be valid for periods from one week to one year.

- Pay as you go (PAYG) – rather than buying tickets online or at the station, passengers can (depending on the location) pay for journeys through contactless payment methods at ticket gates, with the fare they pay determined by when and where they started and ended their journey. PAYG options can include contactless bank card, local schemes (such as Oyster in the London area) and smartcards issued by TOCs.

3.13 In addition to the fare types themselves, passengers (depending on their eligibility) can also purchase a railcard to obtain a discount against the cost of their journey. Table 3.1 lists the main railcards which enable passengers to save on most tickets. The list is not exhaustive; there are other railcards including 11 regional railcards that are not listed below. There are also concessionary travel schemes which are not available from rail retailers such as the Jobcentre Plus Travel Discount card and the HM Forces Railcard.

Table 3.1 The main types of railcard in use in Great Britain

| Railcard | Eligibility | Restrictions and validity | Exceptions to the restriction |

|---|---|---|---|

16-17 Saver Save 50% | Everyone aged 16-17 | ||

16-25 Railcard Save 1/3 | Everyone aged 16-25 Mature students of any age | Min. fare of £12 before 10am Monday to Friday (excluding bank holidays) | Advance fares and July & August |

26-30 Railcard Save 1/3 | Everyone aged 26-30 | Min. fare of £12 before 10am Monday to Friday (excluding bank holidays) | Advance fares |

Disabled Persons Railcard Save 1/3 | People with a disability that meet the eligibility criteria Includes an adult companion | No restrictions | |

Family & Friends Railcard Save 1/3 | Up to 4 adults travelling together with up to 4 children aged 5-15 | Adult must be travelling with at least one child Not valid in London Southeast area during morning peak Monday to Friday (excluding bank holidays) | |

Network Railcard Save 1/3 | Everyone aged 16 and over for travel in London and Southeast area Can buy discounted tickets for up to 4 adults travelling together with up to 4 children aged 5-15 | Min. fare of £13 at all times Not valid before 10am Monday to Friday (excluding bank holidays) | |

Senior Railcard Save 1/3 | Everyone aged 60 and over | Not valid before 10am Monday to Friday in London and Southeast area | |

Two Together Railcard Save 1/3 | Everyone aged 16 and over | Valid only when two named people travel together Valid only on off peak journeys Monday to Friday and anytime during the weekend and bank holidays | |

Veterans Railcard Save 1/3 | Veterans aged 16 and over who have served at least one day in the UK Armed Forces or UK Merchant Mariners who have seen duty on legally defined military operations Includes adult companion | Min. fare of £12 before 10am Monday to Friday (excluding bank holidays) Companion must be travelling with named veteran | Advance fares and July & August |

Overview of terms and conditions

3.14 Travel on the railway, like the purchase of many other products and services, is subject to T&Cs. These set out passengers’ rights and responsibilities when travelling and the restrictions on the type of ticket they have purchased. In purchasing a ticket, passengers enter into a contract with the retailer and the TOC(s) whose services they will be using.

3.15 There are a number of different T&Cs that apply to passengers when travelling across the network, and usually multiple sets apply during the course of the passenger’s journey, creating a layered contractual environment that can be difficult to navigate. Relevant T&Cs could include:

- retailer T&Cs – these form the agreement between the passenger and retailer when using the retailer’s website or app;

- the NRCoT, which form part of the agreement the passenger enters into with the train companies when they buy a ticket to travel on the mainline railway;

- ticket T&Cs – these are specific to the ticket type and include validity restrictions, and are available on the National Rail website;

- railcard T&Cs – these relate to the application of the railcard discount and can include time restrictions and minimum fares;

- TfL Conditions of Carriage – these outline the rights and responsibilities of passengers using TfL services; and

- T&Cs for payment types, e.g. TfL Contactless Cards and Devices Conditions of Use, and Oyster Conditions of Use on National Rail services.

The overarching legal and regulatory context

3.16 The retail of rail tickets is governed by a framework of consumer protection regulation (including the Consumer Rights Act 2015, Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024 and other relevant legislation). Key principles include the following.

- Terms are required to be fair and transparent to ensure that consumers can evaluate the impact of the term.

- Retailers are required to provide ‘material information’, which is the information the average consumer would need to make an informed transactional decision. If this is not provided, this could be classed as a ‘misleading omission’ for the purposes of consumer law.

Information provision

Overview of issue

3.17 Our primary research and engagement with passengers and industry have highlighted a recurring concern regarding the provision of adequate information at the ticket buying stage. Evidence gathered for this review shows that, while there are examples of good practice in information provision, information provided across some retailers and some channels might not adequately set out the key T&Cs and validity restrictions of tickets.

3.18 Through industry engagement we understand that, while some gaps in information can be resolved through changing the information available on websites, apps or TVMs, some gaps are caused by the retail data and systems underpinning the ticket issuing systems used by ticket retailers.

3.19 The provision of material information on ticket restrictions and validity is vital for two reasons. It enables passengers who are intending to pay the right fare for their journey to buy a valid ticket. It also ensures that those seeking to evade fares cannot use the opportunity created by poor information to try to justify travelling without a valid ticket.

Findings

3.20 To assess the provision of validity information to passengers, we undertook three packages of primary research.

- Website and app reviews – these were conducted internally between January and March 2025 to review whether websites and apps provide clear, accurate and timely information throughout the ticket buying process as well as on webpages about ticket types, railcards and T&Cs.

- TVM mystery shopping – ESA Retail (an independent research company that has previously carried out TVM research for ORR) reviewed information provision at TVMs through 500 mystery shops across 19 different TOCs.

- Ticket office visits – these were conducted by ORR staff to understand the systems, processes and training used at station ticket offices to provide information to passengers.

3.21 Our conclusions regarding information provision were also shaped by the findings from the wider work carried out to inform this review, including:

- work undertaken by Savanta to understand the views of revenue protection staff;

- responses to our Call for Evidence;

- responses to our information requests; and

- reviews of previous broader research carried out by ORR and other bodies, such as Transport Focus.

Insufficient information provision on online retail channels

3.22 Our review of websites and apps found that retailers were not consistently providing adequate information on T&Cs or ticket validity restrictions to consumers. We observed this both through the ticket buying process and on the general information pages of retailer websites, such as webpages on different ticket or railcard types.

3.23 Examples of information gaps highlighted through our review of online sales channels included the following:

- the time that Off-Peak and Super Off-Peak tickets are valid is often generic and high-level, with no specific times provided;

- age restrictions for child tickets are difficult to find through the ticket booking process. In some cases, age restrictions are set out across multiple pages on retailer websites with no central source of information; and

- some retailers do not highlight that railcard discounted tickets under £12 cannot be used before 09:30 or 10:00 (depending on the railcard used). Where this information is provided, it is only provided for a selection of railcards in the detailed T&Cs.

3.24 In addition to issues with information provision, our review also identified areas of good practice by some retailers. These include:

- reminding passengers of the restrictions relating to minimum fares when applying a railcard discount – either highlighting in a coloured box that the railcard has been applied and so the ticket is only valid after 10am; or highlighting at the side of the booking flow that a railcard discount has been applied and minimum fare and time restrictions may apply; and

- boxes highlighting the times of other off-peak services on which the off-peak tickets being purchased are valid.

Insufficient information provision at ticket vending machines

3.25 TVMs were originally designed as ‘queue busters’ to allow passengers to make quick and easy ticket purchases at a station, rather than using station ticket offices. ESA Retail’s review found that TVMs were not consistently providing adequate information on T&Cs or ticket validity to consumers.

3.26 Examples of information gaps highlighted through the review of TVMs included the following:

- information regarding the exact time window for off-peak travel is often not available on a TVM. This leaves consumers needing to check other sources of information, such as speaking to station staff (if available), for full details about time restrictions;

- information about railcard restrictions in force prior to 10am on the majority of TVMs, which may contribute to passenger confusion about the validity of their ticket; and

- more than five taps/clicks to access validity information in the ticket selection process for some TVMs, meaning that passengers may not easily find this if they need it.

3.27 While the review found issues with information provision, it also identified areas of good practice at some TVMs:

- some TVMs are clear that they only sell a limited range of tickets and provide information about where a greater range is available;

- some TVMs provide useful information about off-peak restrictions, e.g. a list of which trains are classed as off-peak; and

- some TVMs confirm whether the selected railcard is valid for the ticket purchased.

Retail systems and data contribute to information issues

3.28 Engagement with industry, in particular RDG and ticket retailers, highlighted that the structure of industry systems and the format of data underpinning online ticket sales mean it can be difficult to display full and accurate information regarding ticket validity in a clear, simple and user-friendly way.

3.29 In response to our information request, TPRs and providers of white label retail platforms for the industry provided examples of where, in their experience, industry retail systems were contributing to ticketing issues and confusion. The examples given included:

- the systems allowing passengers to buy tickets that are not valid for their journey (an example includes a passenger being sold a ticket that was not valid for travel on the London Underground although the journey included travel between London Underground stations). This was noted as a particular issue for off-peak tickets by two retailers;

- inconsistent use of the systems by TOCs leading to the wrong fulfilment methods being made available to passengers (for example, providing passengers with an e-ticket, when they are not valid on a particular route); and

- a lack of consistency between the systems setting out validity information for railcards and for tickets.

3.30 Owing to some of the problems emerging from the piecemeal development of industry systems over time, industry retail systems are fed by several different data streams. The data for these is often held in different formats, some of which can be described as outdated (for example, flat text files that do not integrate with each other). This makes it difficult for retailers to extract and present information in a way that is accessible for passengers.

3.31 Within these systems, there is no single source of truth for ticket validity or restriction information. Instead, this is held across several different data sources, aggregated and then presented to the passenger. In addition, information on validity might be specified differently across these different sources of data. This is both a product of the design and content of the different data sets and is affected by how TOCs create fares within the industry systems, using different combinations of restriction codes. An example of this is given below.

3.32 Additionally, the accreditation process for retailers (and the obligations arising from this) is primarily focused on enabling the tracking and allocating of ticket revenue, and on providing accurate and impartial information, rather than on providing information optimally to passengers (as the end users).

3.33 This reflects the need for retailers’ TIS to effectively communicate with the industry system for ticket revenue settlement (LENNON), so that revenues can be collected and distributed correctly across the industry. To ensure this, retailers must use certain industry data systems, prescribed by RDG, when building their TIS. However, this means that, even if a different industry system or data source could provide better information for passengers, retailers would not currently be able to incorporate this system into their TIS and retain their accreditation.

Lack of effective feedback loops to respond to issues identified by front-line staff

3.34 Our engagement with industry and the outputs from the Savanta research found that confusion arising from how ticket T&Cs and validity information have been presented has resulted in passengers travelling with invalid tickets. For example, the Savanta report highlighted issues with:

- passengers not understanding or being aware of restrictions for off-peak tickets; and

- passengers not being clear on the restrictions of Advance tickets bought from TPRs.

3.35 Our engagement with ticket office and revenue protection staff revealed their concerns about information provision when passengers are buying tickets online, in particular split tickets. In these instances, passengers may not be aware that their ticket is a split ticket and this can cause confusion for passengers who believe they need to change trains at the station shown on their tickets (and so get off the train instead of remaining on the same train, and then board the next service for which their ticket is not valid), or when passengers mistakenly board the wrong train.

3.36 While frontline staff are aware of these issues, there is no effective feedback mechanism for this information to be acted on to support continuous improvement.

3.37 This was confirmed through our engagement with TPRs and providers of the white label retailing systems, who corroborated that there is no consistent way of this feedback reaching retailers in order for them to action changes to improve these issues with information provision.

3.38 Responses to our information request show that, while some data sharing agreements exist between TOCs and retailers, these mainly facilitate information sharing regarding ticket fraud. This means that issues commonly seen by revenue protection staff do not routinely become learnings for ticket retailers to drive continuous improvement in how tickets are described online.

Conclusions on information provision

3.39 The nature and scope of this review was not designed to carry out a detailed assessment of retail practices to determine whether a company’s activities or practices align with consumer protection laws. However, we have identified potential issues that may warrant further review and more in-depth analysis in future.

3.40 There is also potential broader harm for industry and taxpayers if retailers are not providing adequate information to consumers:

- it would impact industry revenues if passengers are not buying valid tickets for their journey (and therefore not paying the correct fare). For example, a passenger not being informed of the off-peak time restrictions could mistakenly travel on a peak time train with a cheaper off-peak ticket; and

- not providing information in a way that aligns with consumer law could mean that TOCs are not able to enforce the restrictions on tickets and demand the correct fare. This could both prevent TOCs from recovering their entitled revenue when they stop passengers who are travelling with the wrong ticket or allow those seeking to evade paying the correct fare to do so (by deliberately buying a cheaper but invalid ticket).

3.41 Our Call for Evidence and feedback from revenue protection staff highlighted that issues with information provision and confusion around the validity of tickets have led to passengers being subject to revenue protection action even when it appears they have made genuine mistakes. All of this means there is a need to address the potential for harm to passengers on the one hand and taxpayers, farepayers and the rail industry on the other.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 1 (‘Make buying the right ticket simpler and easier’) addresses issues with retail systems and with information provision to passengers to support consumer law compliance.

- Recommendation 5 (‘Greater coordination, oversight and transparency of revenue protection activity’) covers the need for greater industry coordination to support revenue protection activity, including better data. This includes the need to establish better feedback loops between retail and revenue protection processes to address the issues we noted earlier.

Complexity of ticket T&Cs

Overview of issue

3.42 The second issue we have identified in relation to ticket retailing relates to the complexity of T&Cs and validity restrictions. Throughout our review, it has become apparent that the landscape of T&Cs across the rail industry leads to:

- passenger confusion regarding the validity of tickets;

- layering of different sets of T&Cs;

- challenges regarding consumer law compliance due to the volume and complexity of T&Cs; and

- opportunities for those who are seeking to evade fares to capitalise on this perceived confusion.

Findings

3.43 As noted in chapter 2, we commissioned Illuminas to look at passenger experience and understanding of T&Cs. This work included:

- focus group interviews with passengers across the country covering a range of ages, socioeconomic backgrounds and travel habits to understand passenger awareness of T&Cs and knowledge of ticket validity restrictions;

- in-depth interviews with specific groups of passengers to understand awareness of T&Cs and knowledge of ticket validity restrictions; and

- in-depth interviews with a selection of respondents to our Call for Evidence where confusion regarding T&Cs or ticket validity was the cause of revenue protection action.

3.44 In addition to this specific primary research, other elements of our wider approach to the review provided important evidence regarding our assessment of the clarity of T&Cs:

- Savanta’s research found that frontline revenue protection staff observed that passengers did not understand the ticket they had bought or had not read the T&Cs;

- our engagement with industry stakeholders such as the Rail Industry Fraud Forum, Transport Focus and London TravelWatch highlighted the key issues with T&Cs and ticket restrictions; and

- responses to our information request highlighted the ticket types and restrictions about which both TOCs and retailers receive the most complaints.

Passenger awareness of T&Cs

3.45 The Illuminas report concluded that passengers typically lack awareness of the NRCoT or what it contains and how it relates to their journeys. In focus groups, passengers generally said that they had not heard of the NRCoT and, despite their confidence that they understood the rules of travelling by train, they could not describe its contents.

3.46 This aligns with a publication about consumer understanding of online contractual terms by the UK Government’s Behavioural Insights Team which states that a very small proportion of consumers properly read or understand T&Cs when buying online.

Layering of T&Cs

3.47 When a passenger purchases a rail ticket, they may be bound by multiple layers of T&Cs, each addressing distinct aspects of features of the journey. While these T&Cs might be separate, they collectively contribute to the overall contractual framework for the consumer, and should align with relevant consumer protection laws, ensuring transparency, fairness and clarity in their application. This is a complex environment for any consumer to navigate and better, more innovative ways of clearly communicating material information are needed.

3.48 As set out earlier in this chapter, the NRCoT is not the only set of T&Cs that may apply to a passenger’s journey:

- different types of tickets have their own validity restrictions;

- there are ticket fulfilment requirements for different journeys (for example, m tickets (electronic tickets comprising of a barcode, stored on a mobile device) require validation before use) and across different TOCs;

- railcards have their own T&Cs and can affect the restrictions on tickets; and

- some payment methods have their own T&Cs.

3.49 Passengers on multi-leg journeys may face different T&Cs at different stages of their journey, with rules changing between TOCs and ticket types. As an example, passengers travelling with a railcard on both the National Rail and TfL network (e.g. outer London and the London Underground) could be bound by up to four separate sets of T&Cs. Using contactless or Oyster for this type of journey adds another layer of complexity, as separate T&Cs apply to these: Oyster conditions of use and contactless cards and devices conditions of use. In addition, TfL has separate Conditions of Carriage for all journeys on the TfL network.

3.50 The T&Cs applicable to a passenger’s journey can also be lengthy as well as spread across several documents. For example, the NRCoT comprising of 34 pages, the TfL Contactless Cards and Devices Conditions of Use at six pages, plus scrollable webpages setting out the specific ticket T&Cs and, separately, the railcard T&Cs.

Specific ticket types causing confusion

3.51 In addition to a lack of understanding of the broader T&Cs, Illuminas’ research found that passengers also struggle to understand restrictions linked to some specific ticket types. This is the case for ticket types that have time, route or TOC restrictions.

3.52 While focus group participants were often able to match the ticket types to the definitions, it was not intuitive for passengers, and they were often surprised by the ticket types and the restrictions these had.

3.53 Even when passengers were able to match the ticket types to the definition, they were not able to provide any further detail on ticket validity, such as specifics on the times at which Off-Peak and Super Off-Peak tickets were valid or the exact rules around child ticket age restrictions.

3.54 Through this work and engagement with industry, we have identified that the following ticket types cause particular confusion for passengers.

- Off-peak – Illuminas identified that, while passengers understood off-peak as a concept, they could not identify when an off-peak ticket would be valid or whether this was applicable to evening and well as morning peak times. Industry stakeholders also identified off-peak as problematic given that time restrictions for off-peak tickets vary across the network.

- Advance – Focus group participants were generally aware of Advance tickets and that they could be bought more cheaply, further away from the date of travel. However, some participants did not understand that these tickets were restricted to the booked train service only. From a passenger perspective, the term ‘Advance’ could relate to any ticket type bought ahead of travel, all of which might have different restrictions.

- Return – Engagement with industry highlighted passenger confusion regarding the range of return products for sale, some of which are valid for one day and others that are valid for one month. This was reinforced by case studies from our Call for Evidence, as included in the Illuminas report.

- Child tickets – Different child ticket ages apply across different transport networks, for example bus and TfL networks. This contributes to confusion over what the child age is on the mainline railway.

- Illuminas’ focus groups showed that participants were not always confident on the child ticket age threshold. In addition, our engagement with the Rail Industry Fraud Forum also highlighted that passengers between the ages of 16 and 18 travelling with a child ticket was one of the biggest reasons for ticket irregularities across the network. Some TOCs who responded to our information request reinforced this concern, ranking invalid use of a child ticket as their second most common issue regarding ticket T&Cs.

- The rail industry introduced a 16-17 Saver Railcard that gives 16-17 year olds holding the railcard a 50% discount. This is equivalent to the child discount but requires the passenger to purchase a railcard to have access to the discounted fare. While this has the benefit of discounted fares for this age group (who are predominantly still in education), it creates another opportunity for passengers of any age to apply a higher discount to their ticket, whether accidentally or knowingly.

- Given the costs of administering the 16-17 Saver Railcard as well as the costs of its incorrect usage, there may be a case for reviewing whether there would be overall net benefits from aligning the adult rail ticket age with the legal adult age (18), thereby removing the need for this railcard product.

Railcards

3.55 Railcards have their own T&Cs, in addition to the T&Cs for individual ticket types and the broader NRCoT. As set out earlier in this chapter, these T&Cs impact when and where the railcard can be used and the amount of discount passengers receive.

3.56 A key example is that Anytime tickets under £12 bought with some railcards are not valid before 10:00. This means that railcard T&Cs have a fundamental impact on the validity restrictions of tickets. As set out in chapter 1, there have been high profile cases where this has caused confusion and led to passengers who have mistakenly travelled on these tickets being subject to revenue protection action.

3.57 Another T&C of railcards is that they must be valid both when buying a ticket and when travelling. However, there is currently no way of checking whether a railcard is valid when a passenger purchases a ticket with a railcard discount online, or even whether a passenger holds that railcard at all.

3.58 This allows passengers to apply a railcard mistakenly (including the wrong type of railcard) or apply an out-of-date railcard to their ticket. It also creates an opportunity for a passenger who does not have a valid railcard to deliberately apply a railcard discount that they are not entitled to. When shadowing revenue protection staff, we observed cases where passengers appeared to have done this.

3.59 Some retailers have introduced systems reminder emails to alert passengers when their railcard is close to expiry or has expired. However, this is not common across every retailer.

3.60 Additionally, some railcard T&Cs (such as the 16-25 and 26-30 railcards) contain the following term:

“At the time of printing, the minimum fare is £12. The minimum fare is subject to change during the validity of your Railcard – check website for the most up to date information.”

3.61 This puts the onus on the passenger to check whether the restrictions for their railcard have changed each time they use it.

PAYG travel

3.62 PAYG travel is growing in popularity due to its flexibility, and its use is expected to rise with its upcoming expansion in various parts of England. However, our review of T&Cs and operational rules for contactless and smartcard payments found inconsistencies in how these are communicated to passengers.

3.63 Information provided on the availability of PAYG on applicable journeys is inconsistently communicated on websites. The option to pay with PAYG can appear in either journey planners, on station information pages, during the ticket purchase stage, or not at all.

3.64 We also found that key T&Cs for passengers travelling on the National Rail network in TfL travel zones do not appear in a timely way and is not easy to find when planning a journey or at the ticket purchase stage. We found just one example of a retailer who displayed key payment terms for contactless and Oyster during ticket purchase.

3.65 Information about boundary stations where Oyster is invalid but contactless is accepted is shown in maps such as TfL’s rail and tube services map, and it is also included in the detailed T&Cs. However, TfL’s single fare finder was the only example we found displaying clear contactless information with Oyster restrictions.

3.66 Passengers are also required to use the same card or device (bank card, mobile pay, smartwatch etc) to tap in and tap out. This is because tapping in with, say, a physical card but then tapping out with a device linked to the very same card will register on the system as different journeys. However, our engagement with industry indicated that some passengers are not aware of this. This may lead to them being charged for an incomplete journey, even though they have tapped in and out. Of the five retailer websites we reviewed for contactless and Oyster journeys, only one displayed their payment terms during ticket purchase.

3.67 Our engagement with industry as well as our experience shadowing revenue protection teams indicates that there is confusion among some passengers regarding Oyster and Contactless payment rules around boundary stations. This confusion could result in some passengers being penalised. It is therefore clear that passengers would benefit from better and timely information about the options for different payment methods, when they are available and the key T&Cs which apply to their journey.

Use of industry jargon

3.68 The complexities inherent in the range of ticket validity restrictions and T&Cs is further exacerbated by the use of jargon by industry when describing ticket types or validity restrictions. Illuminas tested a number of different railway terms to gauge passengers’ understanding of them.

3.69 While passengers find some terms, such as ‘valid only via [station name]’, intuitive, informative and easy to understand, others are not clear and cause confusion for passengers, as follows.

- London Terminals – Participants in the focus groups could not identify the stations that would be classed as London terminals. Respondents did not understand whether this was major stations only, or whether the station could have any through trains.

- Valid on any permitted route – Illuminas found that this has significant potential to confuse as passengers did not understand this term or know how to identify a permitted train or route.

- Valid on [TOC name] only – While many respondents found this term somewhat intuitive, others found it surprising and worried about how the restriction might impact them during disruption.

- Engagement with industry and our visits shadowing revenue protection staff across the network highlighted other situations where industry terms are unclear and cause confusion, such as the use of ‘Manchester Stations’ which covers Manchester Deansgate, Piccadilly, Oxford Road and Victoria. Revenue protection officers noted that passengers do not understand that other Manchester stations are not included within this grouping, such as Manchester Airport.

3.70 TVM mystery shoppers who participated in the ESA report research found some of these terms confusing too (see paragraph 4.1.6 of that report).

Conclusion on complexity of ticket T&Cs

3.71 In line with our analysis of the findings regarding information provision, the findings above also pose challenges for the rail industry regarding consumer law compliance. They raise similar issues for industry revenue generation and the potential for intentional fare evaders to exploit the complexities of the system.

3.72 As a result, there is a need to address this complexity to remove the potential for harm to passengers and to the rail industry (and by implication to tax- and fare-payers).

3.73 Separately, this chapter has covered the fact that there is a complex landscape of T&Cs that are not always understood by passengers. While improvements to information provision can help to ensure that passengers are aware of the key T&Cs that apply to their journey, streamlining the T&Cs would help to make them clearer and more accessible for passengers. It would also provide the industry with a stronger foundation for enforcement action against those who deliberately evade paying the correct fare.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 1 (‘Make buying the right ticket simpler and easier’) covers the need to address problems caused by complexity.

- Recommendation 4 (‘Make information on revenue protection easy to access and understand’) discusses the need to make information on revenue protection easy to access and understand. This (among other things) covers ticket T&Cs. As part of this, we consider there should be a review of the NRCoT (and its underlying policies) to take account of the issues we have identified. As we note in chapter 6, RDG is looking at a comprehensive overhaul of aspects of the NRCoT, which could provide an opportunity to do this.

Additional areas for consideration

3.74 Beyond our recommendations, there are three other areas relating to retailing that we think would merit further consideration for action. The first two are areas that we did not have sufficient time to fully consider within the constraints of our review. The third is an issue that interacts with DfT’s consultation on rail reform.

Ticket validity during disruption

3.75 Engagement with passenger bodies and feedback from Illuminas’ research highlighted that passengers can be confused about their ticket validity if their planned journey is affected by disruption. For example, most passengers thought they could use the next train going to their destination, but this is not always the case depending on the ticket they hold.

3.76 We suggest that further work be undertaken to better understand how disruption contributes to passengers travelling with an invalid ticket, and what aspects of ticket validity during disruption passengers find most confusing.

3.77 This would support the development of better information and communication for passengers as to what their onward travel options are during disruption, while also reducing the likelihood that they innocently end up travelling with an invalid ticket.

Ticket fulfilment

3.78 Engagement with rail staff and feedback from the Illuminas research suggested that passengers can be confused by the fulfilment rules for their ticket. By fulfilment, we mean the process by which a purchased ticket is delivered to the customer. Sometimes there are restrictions on how retailers can fulfil tickets, often related to gateline technology in operation at the stations along their journey.

3.79 For example, for those passengers whose ticket provides for travel across London, the London Underground gatelines do not accept barcode tickets. As such, the retailer will usually need to fulfil the ticket purchase as a paper ticket. This can lead passengers who are used to a digital ticket to not realise that they needed to collect their ticket at the station.

3.80 We also found during our research and engagement that some passengers buying their tickets online (from a website or app) assume that their ticket would be fulfilled as a digital ticket. But some tickets must be collected from a TVM before travel. This was seen as counter-intuitive when the purchase was made online.

3.81 We suggest that further work is undertaken to understand how fulfilment requirements contribute to passengers travelling with an invalid ticket, what the key areas of confusion are, and what actions can be taken to address these.

Changes to the licensing and accreditation of retailers

3.82 As set out earlier in this chapter, rail ticket retailers are licensed and accredited by RDG. This process is focused on tracking and allocating ticket revenue and ensuring that retailers can use, connect and share data with industry systems. This process does not currently focus on the impact of systems on the end user.

3.83 Given this, there is a case for considering changes to this licensing and accreditation structure to include a focus on ensuring accurate and complete information provision. This could support compliance with consumer law as well as improved clarity of information for passengers, as well as supporting revenue protection more broadly.

3.84 However, this may require legislative change. Also, and as noted above, the licensing and accreditation of rail retailers is currently under review in DfT’s consultation on the future structure of the railways under GBR.