Introduction

5.1 As set out in chapter 4, each TOC has its own revenue protection policy and practices and there are a range of enforcement approaches. This also extends to approaches to prosecuting passengers for fare evasion and ticketing offences.

5.2 A passenger may be prosecuted after a member of revenue protection staff finds them without a valid ticket and reports them for a suspected fare evasion offence. Alternatively, a TOC may decide to prosecute a passenger who was issued a penalty fare or UFN if they do not pay within a certain amount of time. The flowcharts in Annex E set out the various routes to prosecution following the issuing of different notices such as penalty fares, UFNs, FTP notices and TIRs.

5.3 As illustrated in the flowcharts, there are a number of routes and decision points that may lead to prosecution and outcomes such as settlement, conviction or acquittal.

5.4 This chapter is focused on the following item from the terms of reference:

- The prosecution process – the circumstances in which prosecution is appropriate to the offence. This includes the requirements on prosecutors, for example the Full Code Test.

5.5 It covers:

- options and approaches to prosecution;

- TOCs’ approach to the charging decision; and

- assessing the scale and impact of prosecutions.

5.6 Where relevant, it also considers other aspects from our terms of reference as they apply to prosecutions, including ‘operator assurance and accountability’, the ‘communication of the enforcement approach’ and ‘operator and taxpayer need to protect revenue’.

Options and approaches to prosecution

Overview of issue

5.7 Each TOC has its own policy for how and when it uses prosecution as part of its revenue protection approach. Processes for reporting suspected fare evaders for prosecution or consideration for prosecution vary between TOCs. The options available also vary according to the training or role of the member of staff who has identified the situation. In all cases, bringing criminal proceedings requires evidence of the suspected offence in a format which can be put before a court.

5.8 This section provides an overview of TOCs’ approaches, the toolkit available, investigative and prosecution processes, including the SJP, and the interaction between penalty fare appeals and prosecutions.

Findings

Overview of approaches to prosecution

5.9 There is no national or agreed industry policy or guidance to guide TOCs’ approach to prosecution, either at Great Britain-level or within any of its constituent nations. In their response to our request for information, some TOCs referred us to historic documents.

5.10 These include the Association of Train Operating Companies’ (ATOC’s) ‘Approved Code of Practice Arrangements for travel ticket irregularities 2013’ and the ATOC ‘Guidance Note – Prosecution Policy’. ATOC was not a regulatory body and compliance with these documents was not mandated. Both documents have subsequently been withdrawn, although they continue to influence some TOCs’ approaches.

5.11 Broadly speaking, criminal prosecutions are used to address societal harm, whereas civil legal action provides for resolving disputes between individuals or companies. TOCs give different prominence to the use of criminal prosecution in their approach to revenue protection, including how routinely it is used, as demonstrated by Figure 5.1 further below (see paragraph 5.107 onwards). We found that 18 TOCs currently use prosecution as part of their revenue protection approach in some way, as demonstrated below.

5.12 By contrast, only a handful of TOCs provided evidence of recovery of unpaid fares via the civil courts, usually in addition to prosecution. This includes using the civil courts to recover unpaid penalty fares or to pursue cases which have exceeded the six-month statutory time limit for prosecution of summary offences.

5.13 In general, TOCs who prosecute typically use either an in-house prosecutions team or a third-party company to prosecute on their behalf. However, London Overground and Elizabeth line (as TOCs contracted by TfL) pass any cases of suspected fare evasion which require further action to TfL for it to deal with (TfL is a public prosecutor).

5.14 High-value rail fraud, including persistent fare evasion, may be referred to the BTP for investigation and further action via the CPS, or TOCs may investigate and prosecute privately.

5.15 Some TOCs do not prosecute criminal offences themselves, including the two publicly owned TOCs in Scotland. Scotland has a different legal system to England and Wales and under Scots Law private prosecutions are exceptional. In practice, this means reporting the suspected fare evader and offence to the BTP for prosecution via the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service.

5.16 A number of open access TOCs have made commercial and operational decisions also not to use criminal prosecutions. Reasons include operating a “buy on board” policy and having high ticket compliance rates due to the nature of the service and other ticketing controls.

Use of third-party revenue protection contractors

5.17 Around half of TOCs engage a third-party revenue protection company to support their wider revenue protection activities. Eight TOCs use one of two companies to support all or part of their prosecution activity. Each company has different responsibilities, accountabilities and decision-making processes, and these vary by TOC. The range of activities outsourced includes administrative support, correspondence, assessing which cases to progress and preparing and presenting cases at court.

The Prosecution Toolkit

5.18 As outlined in chapter 1, TOCs generally prosecute suspected fare evaders under the applicable railway byelaws or RoRA. Some offences such as sections 5(3)(a) and 5(3)(b) of RoRA require intent to avoid paying the fare. Whereas, to prove an offence under section 5(1) RoRA or byelaw 18, the prosecutor does not need to prove intentional fare evasion. This simply means that a passenger may commit an offence by not holding or being able to show a valid ticket. The intention of the passenger is irrelevant as this is a strict liability offence.

5.19 However, under byelaw 18 there are some specific limited defences available to a passenger who is unable to produce a valid ticket. These are:

- there were no ticket selling facilities available at the journey’s start;

- a notice was displayed permitting journeys to be started without a valid ticket; or

- an authorised person gave permission to travel without a valid ticket.

5.20 If intentional fare evasion is suspected and a TOC decides to pursue prosecution, there is no requirement to pursue a RoRA section 5(3)(a) offence. It may choose to pursue a byelaw prosecution instead. Similarly, revenue protection staff may initially investigate a RoRA section 5(3)(a) offence but the TOC may subsequently decide to prosecute a byelaw offence, for example if there is insufficient evidence of intent.

5.21 Strict time limits apply to most fare evasion offences, with a requirement to bring charges within six months of the date of the offence. The prosecutor must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the passenger has committed the criminal offence. The prosecutor may seek compensation and prosecution costs and, in contrast to claims in the civil court, the TOC does not have to pay a fee to the court for bringing the case.

5.22 In a civil claim, time limits are relatively long, and the TOC must prove (on the balance of probabilities) that the passenger owes it money and justify the remedy it is seeking, i.e. how much compensation it is due. This can include legal costs incurred in bringing the claim, which in many cases are fixed. In a civil claim, the amount awarded by the court is to be paid to the TOC, whereas a person convicted of a criminal offence may be ordered to pay various different sums to different parties (as discussed in paragraph 5.138 below).

Interaction with penalty fares

5.23 As stated above, TOCs may decide to prosecute a passenger after they were issued a penalty fare but failed to pay it. However, the 2018 Regulations and the accompanying explanatory memorandum contain ambiguities which have affected how TOCs (and third-party contractors acting on their behalf) have approached the prosecution of passengers who were issued a penalty fare, particularly where those passengers appealed the penalty fare and their appeal was rejected.

5.24 In February 2025, the Chief Magistrate ruled on whether an unsuccessful penalty fare appeal provided protection from prosecution for certain fare evasion offences. He ruled that criminal prosecutions can be brought following a penalty fare appeal being rejected.

5.25 Although not binding, this ruling provides persuasive clarity that, where a passenger’s penalty fare appeal has been dismissed, a TOC may prosecute. (Where an appeal is upheld, the passenger is immune from prosecution.) Nevertheless, ambiguity and uncertainty relating to the 2018 Regulations have impacted TOCs’ approaches to prosecution, with some TOCs opting not to prosecute when a passenger has appealed a penalty fare, while others have chosen to prosecute in the same circumstances.

Prosecution procedure and process

The Single Justice Procedure (SJP)

5.26 The SJP is a streamlined process used in Magistrates’ Courts in England and Wales to handle less serious non-imprisonable offences committed by adults. It allows cases to be dealt with by a single magistrate without the need for a court hearing, except if the defendant pleads “not guilty” or chooses to attend court instead. Other safeguards within the SJP to protect defendants’ right to a fair trial include the ability to opt for a full hearing, provide mitigation and re-open proceedings if they were not aware of the SJP proceedings against them.

5.27 It has been suggested that the SJP’s high non-response rate and short timeframes for action contribute to defendants being convicted in their absence without their knowledge. As highlighted in chapter 4, cases reported via the press and our Call for Evidence indicate this has occurred in some TOC prosecutions.

5.28 Since April 2016 TOCs have been permitted to use the SJP to prosecute offences under railway byelaws (including the Railway Byelaws 2005 and Merseyrail Railway Byelaws 2014). TfL, as a public prosecutor, has been authorised to use the SJP since 2015 for any offence that meets the criteria for its use. This includes Transport for London Railway Byelaw 2011 offences.

5.29 As noted in chapter 1, between 2018 and 2023 eight TOCs prosecuted just over 59,000 cases under RoRA, primarily section 5(1) but also section 5(3). The Chief Magistrate ruled in August 2024 that, because TOCs do not have authority to prosecute RoRA offences via SJP, these prosecutions were null and void.

5.30 Among the 18 TOCs that prosecute, all use the SJP to some extent. Five use the SJP exclusively, while the rest prosecute using a combination of SJP and full Magistrates’ Court procedure. Of the 13 TOCs who use a combination of SJP and full Magistrates’ Court procedure prosecutions, all but two use the SJP for most of their prosecutions. Some reserve SJP for certain cases, for example for bringing byelaw prosecutions against passengers who have failed to pay a penalty fare.

Common Platform

5.31 In 2020, HMCTS began rolling out a new digital case management system called ‘Common Platform’. The system allows prosecutors to: send cases to the court when they are ready; access and manage cases in real time; and receive case results instantly, while defendants can enter pleas and mitigation online.

5.32 Two TOCs currently use Common Platform and two TOCs use it indirectly, via TfL. These prosecutors only use Common Platform for byelaw offences prosecuted under the SJP. Other TOCs are in the process of transitioning to the new platform and more may follow as the system is rolled out more widely.

5.33 Common Platform allows for integration between TOC systems for recording, reporting and processing suspected fare evasion offences and court systems. This means that a suspected offence reported by a frontline member of staff can be allowed to automatically progress to charge without a manual review of the case.

5.34 In practice, TOCs using the system may configure their processes to provide safeguards and opportunities to review whether to progress the case. For instance, we found that one TOC using Common Platform will issue an SJP notice automatically 21 days after a suspected offence is reported if there is no response by the passenger to the TOC’s correspondence requesting a financial settlement. If a passenger settles, contacts the TOC with mitigation at any time, or enters a “not guilty” plea, the TOC will review the case to decide whether to continue or withdraw.

5.35 TOCs using Common Platform consider that it has reduced their administrative burden and meant fewer cases were becoming time-barred by reaching the six month statutory limit for prosecuting summary offences. TOCs have adapted their processes around the system, for example sending extra letters to suspected fare evaders to request settlement or introducing manual reviews to prevent cases going straight to trial after a plea is entered.

5.36 The transition to integrated digital case management via Common Platform allows prosecutors to reduce administrative burden and cost. This, in effect, may make it easier for TOCs to prosecute suspected fare evaders. There is some evidence that the move to Common Platform may correlate with higher prosecution rates. For one TOC prosecutor, the number of charges brought against passengers increased by eight times in the year they began using the new system.

Approach to investigation and training

Approaches to investigating and gathering evidence

5.37 At least 12 out of the 18 TOCs who prosecute fare evasion offences employ or contract frontline and back-office staff who are trained and authorised to gather evidence of suspected offences in accordance with the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) and associated codes of practice. This includes investigating whether there was intent to avoid the fare.

5.38 Rail staff and third parties working on their behalf do not have police powers of arrest. However, where deliberate fare evasion is suspected, appropriately trained revenue protection staff may obtain evidence by questioning, i.e. conducting voluntary interviews under criminal caution, both on-train and at scheduled interviews. Alternatively, depending on circumstances, TOC policies and processes, role and level of training, rail staff may record details of suspected fare evasion or other irregularity without conducting an interview under caution.

5.39 Both frontline and back-office staff may gather other evidence to inform an investigation into suspected fare evasion, including CCTV, body worn camera footage, tickets and railcards, and reviewing systems data and journey history.

5.40 Processes for reporting suspected fare evaders for prosecution or consideration for prosecution vary between TOCs. The options available also vary according to the training or role of the member of staff who has identified the irregularity. In all cases, bringing criminal proceedings requires evidence of the offence in a format which can be put before a court. In practical terms, as a minimum, this includes a witness statement from rail staff detailing the offence, known as an “MG11” (MG stands for “Manual of Guidance” and designates a series of criminal case file forms which are used in England and Wales as part of the National File Standard used in preparing and progressing criminal cases).

5.41 Exactly how and when any MG11s are produced varies between TOCs and depends on the circumstances of the case. This can include MG11s produced automatically following frontline staff inputting data into a digital device or producing an MG11 from an existing TIR for more straightforward byelaw offences. Where additional details of the offence or investigative steps are required, frontline staff may manually produce MG11s. Back-office staff may also produce MG11s, for instance to prosecute a passenger who was originally reported via another mechanism (e.g. a penalty fare notice which remains unpaid).

5.42 Regardless of how an MG11 is generated, its production does not necessitate a prosecution or constitute a charging decision. The charging decision is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Information for passengers on prosecutions and opportunities to provide mitigation

5.43 There has been public concern regarding the SJP beyond the rail sector, including examples of people prosecuted under the SJP where the mitigation they provided indicated a prosecution was not in the public interest.

5.44 There is no agreed industry policy or process on what information should be provided to passengers reported for a suspected fare evasion offence, or for how a passenger may provide mitigation. This contrasts with penalty fares, which have clearly defined information requirements contained within the relevant regulations, as well as an independent appeals process. It also contrasts with other sectors. For example, statutory guidance governing environmental enforcement prosecutions by local authorities advises those authorities to operate processes to consider mitigation and lines of defence.

Good practice: communicating next steps to passengers

Some TOCs provide passengers who are reported for consideration of a fare evasion offence with a slip providing details of the interaction and how to get in touch to provide mitigation or to dispute the allegation.

5.45 Nevertheless, among almost all TOCs who prosecute, we found evidence indicating they will make one or more attempts to contact the passenger prior to bringing charges, including to invite any mitigation or other representations. Although TOCs’ approaches to corresponding with passengers regarding prosecution varies, including how many attempts at contact they make and how much time they allow for mitigation, we consider attempts to contact individuals to invite mitigation to be good practice which addresses some of the broader concerns regarding the SJP.

5.46 Despite this finding, via our Call for Evidence, several passengers expressed surprise or dismay at the first communication after an incident being a court summons or finding out about a prosecution after they were convicted in their absence. However, it is not clear whether these reflect TOC processes or other issues, including correspondence which was lost in transit or left unread.

5.47 Some respondents facing fare evasion prosecutions also stated they found it difficult to contact the TOC or the third-party company handling the prosecution:

Varying levels of training and qualifications amongst TOC prosecutors

5.48 As private prosecutors, TOCs are not regulated in the same way as crown prosecutors, or subject to the same professional qualification and training requirements. Industry stakeholders such as the Rail Industry Fraud Forum have developed some formal qualifications for rail staff involved in investigating revenue protection offences. However, there is currently no formal revenue protection qualifications pathway.

5.49 TOCs employ prosecutions staff from different professional backgrounds and with various levels of legal or investigative training. This includes backgrounds in revenue protection, BTP, legal services and the judiciary.

5.50 Some TOCs have formal training requirements for their internal prosecutors, including requirements to hold a Bachelor of Law Degree (LLB) or specific advanced qualifications in investigations. Other TOCs referred to relevant qualifications either being held or pursued by internal staff.

5.51 However, the majority appear not to require any formal qualifications or accreditation for their prosecutions staff, relying instead on various combinations of on-the-job training and in-house or externally delivered training. Where TOCs provided information on the length of internal training, this varied considerably, from five days to three months. Where decisions on prosecutions were made by a third-party contractor, the level of training was in some cases less clear, for example referring to unspecified “relevant legal training”.

5.52 Some TOCs may instruct external barristers to present cases in court, particularly in contested or complex cases. However, we understand use of lay prosecutors by TOCs and third-party contractors is common practice across the industry.

5.53 Prosecutions carry a degree of risk for both passengers and industry, and errors and mistakes can be costly to fix. It is therefore important that staff have the necessary training and knowledge to carry out their role. This includes knowledge of relevant legislation and procedure, to identify: (i) whether to prosecute; (ii) for what offence; and (iii) via which procedure (e.g. full Magistrates’ Court procedure or via SJP). Prosecution staff with less experience, training and qualifications may be at greater risk of procedural errors. We therefore welcome the work of the Rail Industry Fraud Forum towards developing recognised qualifications for rail staff.

5.54 However, we cannot conclude that the variable level of training and qualifications amongst TOC prosecution staff has led to adverse outcomes. In the case of the unlawful SJP prosecutions, it should be noted that these cases were considered (and the legal issue not identified) over a number of years by magistrates supported by legally qualified advisors.

5.55 TOC prosecutors are bound by the same legal requirements on the police and CPS in respect of criminal evidence, disclosure, retention, confidentiality and court procedure. The industry must ensure that these essential requirements and safeguards are understood and complied with by its staff and those acting on its behalf.

Conclusions on options and approaches to prosecution

5.56 While we have identified areas of good practice, there is a proliferation of different processes and approaches among TOCs and a lack of clear, consistent principles (in contrast to comparable sectors like local authority parking and environmental enforcement). This has been compounded by ambiguity in the 2018 Regulations on penalty fares, leading to further inconsistency as TOCs have interpreted the legal framework differently. This is likely to contribute to inconsistent outcomes for passengers depending on which TOC they have travelled with, and a perception of arbitrariness or unfairness among passengers.

5.57 Revenue protection, including TOCs’ prosecution toolkit, has evolved incrementally over a long period of time. While there have been consultations on some elements (such as the penalty fares regime), we are not aware of any overarching or holistic policy review or consultation by any UK government. Some policy interventions, such as legislative reforms to penalty fares, appear to have intended greater protection for passengers who have made an ‘honest mistake’.

5.58 However, strict liability offences such as byelaw 18 allow TOCs to prosecute passengers where there is no evidence of intent or financial loss and provide passengers with very limited defences. This may empower TOCs to take action against deliberate fare evaders without the challenge of proving intent. But, as noted in chapter 4, it also puts passengers who have made an honest mistake at risk of prosecution. Following the introduction of the SJP, it has arguably become easier for TOCs to prosecute. The transition to digital case management via Common Platform has the potential to make prosecution easier still.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 2 (‘Strengthen consistency in how passengers are treated when ticket issues arise’). This includes establishing consistent principles as part of a new governance framework for revenue protection.

- Recommendation 5 (‘Greater coordination, oversight and transparency of revenue protection activity’). Among other things, this proposes that – as a longer-term activity – there should be a review of all the relevant legislation relating to revenue protection, to simplify, clarify and provide greater consistency across the sector.

TOCs’ approach to the charging decision

Overview of issue

5.59 A crucial step in any prosecution is the decision on whether to bring charges against an individual who is suspected of an offence. This is known as the charging decision. To reach a charging decision and determine how best to progress a case, prosecutors may apply a formal test, asking themselves one or more questions to decide what action to take.

5.60 Prosecutors may decide to prosecute, or that the public interest is served best by taking no further action or resolving a case in a different way, without going to court. In the context of revenue protection, this may take the form of an out-of-court settlement, i.e. a financial payment from the passenger suspected of a fare evasion offence to the TOC concerned, on the understanding that charges will not be pursued.

5.61 This section considers TOCs’ approaches to the tests which TOCs apply to decide what action to take, including the circumstances in which out-of-court settlements may be sought and the approach taken to calculating them.

Findings

The test for prosecution

The Code for Crown Prosecutors and the Code for Private Prosecutors

5.62 As with prosecution more generally, there is no industry-wide or national policy on the test TOCs should apply to decide whether to prosecute an individual. Crown prosecutors in England and Wales (the CPS) apply the Full Code Test defined in the Code for Crown Prosecutors. However, TOCs and those acting on their behalf are not bound by it.

5.63 In Scotland, the relevant test for prosecution is applied by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. This applies its Prosecution Code which is functionally similar to the Full Code Test. As TOCs in Scotland do not act as prosecutors, this section is focused on TOCs in England and Wales.

5.64 The Full Code Test includes two stages, the evidential stage and the public interest stage. To pass the first stage, there must be enough evidence to make it more likely than not that a court will convict the suspect. If the first stage has been passed, the prosecutor must consider if a prosecution is in the public interest. This includes considering the seriousness of the offence, the harm caused, and whether prosecution is proportionate. The CPS’s Full Code Test provides a robust and high-quality framework for decision-making, and we consider the application of this test (or a closely equivalent test) a marker of good practice.

5.65 The Private Prosecutors’ Association’s (PPA’s) Code for Private Prosecutors notes that it is good practice for private prosecutors to apply the Full Code Test. This is because CPS’s guidance on private prosecutions provides that if the CPS reviews a private prosecution case and finds either the evidential or the public interest stage of the Full Code Test is not met, then it should take over and stop the prosecution. Membership of the PPA is voluntary, as is adherence to its code.

TOCs’ approaches

5.66 We found significant variation in TOCs’ approach to the test for prosecution.

- Two thirds of TOCs that prosecute provided evidence of a formal test which was applied to determine whether to bring charges. In most cases, the tests defined by TOCs were similar to the Full Code Test, for example containing both an evidential and public interest test. This included one TOC which stated it applies the CPS Full Code Test, and one TOC which referred to the Code for Private Prosecutors.

- In the case of four TOCs, we did not find evidence of a formal test for prosecution. For two others, it was unclear whether a formal test was in use or exactly what test was being applied in practice.

5.67 Several TOCs defined a test which had clear, sequential evidential and public interest stages as well as relevant guidance on key concepts and considerations. Among others, we identified several areas for improvement, including clarity on whether evidence and public interest are considered sequentially and what factors to consider when assessing public interest.

5.68 In some cases, it was unclear who makes a charging decision and at what stage. This was particularly the case for those TOCs that have outsourced some or all charging decisions to a third-party contractor. As discussed above, the training and qualifications of the prosecutors who apply the test also vary.

Good practice: TfL on behalf of Elizabeth line and London Overground

Elizabeth line and London Overground (both contracted to TfL) may refer suspected fare evasion to TfL which then brings any prosecutions on their behalf. TfL’s approach to prosecutions, including its test for prosecution, is clearly defined in its publicly available Revenue Enforcement and Prosecutions Policy. The policy provides a consistent framework for decision-making across all of TfL’s public transport networks, including a two-stage test for prosecution and clearly articulated public interest considerations.

Evidence of passengers being prosecuted where the public interest is unclear

5.69 While individual case studies provide informative illustrations of passengers’ experiences and outcomes, it is important to note that we have not conducted a detailed case review. Therefore, it would not be appropriate for us to definitively conclude on the appropriateness of a TOC’s decision-making in any individual case.

5.70 Nevertheless, responses received via our Call for Evidence indicate that in some cases TOCs have brought prosecutions where, although the passenger may have technically committed an offence, the public interest in prosecution is questionable. This includes respondents who reported facing prosecution for incidents where there was no apparent loss to industry, such as:

- a passenger who had a 26 to 30 railcard but when booking their ticket accidentally selected a 16 to 25 railcard discount, which entitled the passenger to the same saving. Although the ticket was technically invalid, the amount paid for the ticket was identical; and

- a passenger whose printed e-ticket was water damaged so could not be scanned by a member of rail staff, despite subsequently providing proof of a valid ticket for the journey.

5.71 Recent press coverage has also highlighted cases of passengers who purchased tickets online but either did not or were unable to collect them from a station and were subsequently subject to fare evasion prosecutions.

5.72 Other Call for Evidence responses provide examples of passengers who appear to have made a genuine mistake which has caused minimal loss to industry and where it is unclear that prosecution was a proportionate response. Examples include passengers prosecuted for travelling when a railcard or weekly season ticket had very recently expired, for instance the day before travel.

Assessing harm and risk

5.73 Without a consistent test for prosecution across industry, passengers are likely to face inconsistent outcomes from revenue protection enforcement by different TOCs. In the absence of a consistent test for prosecution, it appears that some fare evasion prosecutions have been brought against passengers where the public interest case was questionable. While case studies from our Call for Evidence are anecdotal, this appears to apply to more than just one or two isolated cases. Deficiencies or inconsistencies in TOCs’ tests for prosecution increase the risk of such prosecutions and potential harm.

5.74 In January 2025, Transport Focus made a series of recommendations relating to revenue protection to improve the passenger experience. Among these was a recommendation that there should be no penalties in “no net loss to industry situations”. Our view is that any assessment of the public interest in prosecuting suspected fare evaders should consider whether any harm, i.e. loss to the industry, has occurred. If there is no evidence of loss to the industry, it is unlikely that a prosecution will be in the public interest.

5.75 A lack of a consistent test across TOCs may contribute to a perception of arbitrariness or unfairness among passengers. It risks adverse outcomes for passengers who have made an honest mistake and reputational harm to industry.

5.76 Aligning with the CPS’s Full Code Test would provide safeguards against prosecuting passengers when it is not in the public interest. In addition, this consistency would ensure that similar rigour and process is being applied whether a prosecution is being brought by a TOC, or by BTP (if a case is referred). It would also lessen the risk that the CPS, if it decided to review a TOC’s prosecution, would step-in to stop the case proceeding.

Out-of-court settlements

5.77 There is no national policy or guidance governing how TOCs may or should use out-of-court settlements and they do not fall within the statutory out-of-court disposal schemes created by the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022. The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) has published guidance on community resolutions, a form of non-statutory out-of-court disposal which may include interventions such as compensation for damage or loss. However, it is neither binding on, nor directly applicable to, TOCs.

TOCs’ approach to out-of-court settlements

5.78 Almost all TOCs who prosecute fare evasion offences use out-of-court settlements. Half of these provided evidence indicating a clear focus on or presumption in favour of settling out-of-court. Some TOCs’ policies appeared neutral, where out-of-court settlement was an option but not an indicated preference.

5.79 For a small number of TOCs their stance was unclear. In some cases, TOCs have policies to guide the circumstances in which they may or may not consider a settlement. Examples include considering settlements only where there is no evidence of deliberate intent to avoid paying the fare or it is the passenger’s first offence.

Seeking settlements where the evidential test was failed

5.80 Based on the evidence submitted by TOCs, five have a written policy indicating they may pursue a settlement or financial payment in cases which have failed their evidential test for prosecution. For instance, one such policy stated, under the heading “settlements”:

“Cases may be disposed with by way of a financial payment and are a private matter between prosecutions and the passenger if […] the case failed the Evidential Stage of the Full Test Code [sic] (Stage 1).”

5.81 Another TOC’s policy listed the criteria to meet the standard for prosecution as including the question:

“Is there sufficient evidence to prosecute? If the answer is no, then a settlement will be offered.”

5.82 We do not know how such requests for settlement or financial payments are communicated to passengers in practice and have not requested this information due to the time constraints of our review. However, if a TOC has assessed that it does not have sufficient evidence to prosecute, we consider that it would be unreasonable and without basis to request a financial settlement from a passenger who is under the impression that they may be prosecuted if they do not settle.

5.83 There is no suggestion that it would be unreasonable for a TOC to request payment from a passenger if the circumstances and potential consequences are clearly laid out. In such a case this would not include prosecution but could include civil legal action.

5.84 We have not seen evidence of how frequently such policies are put into practice and cannot state whether any unreasonable treatment of passengers has occurred. Nevertheless, such policies present a risk of unfairness to passengers if not communicated appropriately. They are also out-of-step with policing practice: NPCC Community Resolutions guidance clearly states that a requirement of an out-of-court disposal is that a crime has occurred and there is evidence to prove it.

How the settlement is calculated

5.85 Seven TOCs provided a clear methodology for calculating the out-of-court settlement amount, specifying that this would consist of an administrative fee plus the total of any outstanding fares. Of these, two provided more detailed evidence of which specific costs are factored into the administrative elements of their out-of-court settlements, with one of these providing an itemised and costed breakdown. We consider this to be indicative of good practice.

5.86 From the submitted documents it was unclear exactly how 9 out of the 16 TOC prosecutors who use out-of-court settlements calculate the amount they request. However, most provided evidence indicating that their standard out-of-court settlement amount was the same or similar to the costs and compensation they would claim at court (i.e. costs of £125 to £185, plus the value of any unpaid fare).

5.87 We understand that TOCs may seek a higher out-of-court settlement if a passenger seeks to pay a settlement later in the process, which reflects higher costs incurred in handling the case up to that point.

5.88 Via our Call for Evidence, respondents reported a very small number of out of-court settlements where the settlement amount was many times higher than the outstanding fare and significantly higher than the administrative portion of other settlements of which we have seen evidence.

5.89 After instructing solicitors to negotiate with the TOC, one passenger reported making a settlement of £750 for a single instance of an invalid railcard. Another provided evidence of a £580 settlement offer following a fare discrepancy of approximately £10.

5.90 While it may be that these settlement amounts are reflective of costs incurred in handling these cases and liaising with solicitors, both respondents perceived the outcome as unfair. We note that adding significant administrative fees where passengers plead their case may risk creating disincentives to doing so.

Key principles

5.91 We recognise TOC prosecutors may consider that, in some circumstances, payment of compensation and costs by a passenger suspected of fare evasion may serve the public interest better than a prosecution.

5.92 It is up to TOCs to decide whether to restrict their ability to prosecute suspected fare evaders by entering into a settlement agreement. In principle, it is for the passenger and TOC to mutually agree a settlement amount. However, TOCs should not use the prospect of prosecution to leverage a higher settlement. While we have not found evidence of such conduct, it is important to recognise that using the prospect of prosecution in this way could present legal risks, and TOCs could face challenges in enforcing disproportionate sums.

5.93 If TOCs wish to pursue a financial settlement as an alternative to prosecution, we are supportive of the approach taken by most TOCs. This is to define the settlement amount to reflect the cost of administration plus the outstanding fare and/or requesting a settlement of similar value (or less) than the costs and compensation for which they would apply at court.

Conclusions on TOCs’ approach to the charging decision

5.94 TOCs are not bound by the Code for Crown Prosecutors or required to apply the Full Code Test. Nevertheless, there are good reasons for TOCs to apply or align with it, and it is positive that a number of TOCs already apply a formal test for prosecution which involves considering both evidence and public interest.

5.95 However, there is some evidence that the industry may have brought some prosecutions where the public interest is unclear. This is perhaps unsurprising given the lack of a consistent, robust and transparent decision-making framework.

5.96 Any framework for making decisions on whether to prosecute should encompass alternatives to prosecution, such as out-of-court settlements. Although TOCs’ use of these alternatives to prosecution appears largely reasonable and consistent in practice, TOCs should provide greater assurance to passengers and the public by articulating the principles which underpin their approach, as well as by ensuring that it aligns with best practice and mitigates any risk of unfair treatment.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 3 (‘Introduce greater consistency and fairness in the use of prosecutions’) addresses this issue, including the urgent need for the industry to adopt a consistent test for prosecution and best practice principles for out-of-court settlements, with a view to achieving more consistent outcomes for passengers.

5.97 This would be railway-specific and additional to any mandatory code of practice for private prosecutors which may result from the Ministry of Justice consultation on oversight and regulation of private prosecutors (as discussed in the executive summary).

5.98 The public interest factors as part of a test for prosecution would sit alongside the introduction of an escalatory approach for dealing with ticket irregularities (discussed in chapter 4 and Recommendation 2) to better protect passengers and ensure consistency and fairness in treatment.

Assessing the scale and impact of TOC prosecutions

Overview of issue

5.99 Currently, there is no requirement for public or cross-industry reporting on revenue protection prosecutions. The only publicly available data on fare evasion offences prosecuted under railway legislation is MoJ published Official Statistics. The level of aggregation in this data between different offences makes meaningful analysis difficult.

5.100 While we asked TOCs to provide prosecution data to us as part of our information request, the quality of this data was mixed and we are aware TOCs take different approaches to the collection and recording of this data.

5.101 This section analyses the available data, considers the data challenges and the impact of an increased number of prosecutions on passengers, industry and taxpayers.

Findings

Assessing prosecutions with quantitative data

The data and our approach

5.102 The information request we issued to TOCs asked for detail on the type and volume of prosecutions brought by TOCs, the level of third-party contractors’ involvement in these and the financial recovery from these proceedings. We requested all available data between the rail year 2016-17 up to December 2024 (nine months of rail year 2024-25).

5.103 There were limitations in the data received from TOCs (such as the unavailability of data from prior to a change in franchise and inconsistencies in data collection methods). Given this, we also analysed MoJ published Official Statistics on Magistrates’ Courts prosecutions. As these are Official Statistics, they merit greater confidence and weight in terms of their validity and robustness.

5.104 When comparing these two datasets, we identified that, at a high level, the information for charges brought is broadly consistent in recent years but that there is significant variation between the MoJ published Official Statistics and TOCs’ convictions data. As such, we have only used the data provided by TOCs to analyse the charges brought against passengers for the rail year 2023-24 (1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024). (We have excluded Merseyrail from this analysis as the way it records and reports charges is different from other TOCs and the total charges figure it provided in its response to our information request was not meaningfully comparable.) We have used the MoJ published Official Statistics for all other analysis on prosecutions.

5.105 While MoJ published Official Statistics on Magistrates’ Court charges and convictions is more reliable, it has other limitations. The data also includes prosecutions for non-ticketing and other offences which are outside of the scope of this review. Nonetheless, it is useful in showing the number of prosecutions brought by TOCs and in identifying trends.

5.106 The use of third-party companies to prosecute suspected fare evaders on TOCs’ behalf appears to exacerbate the data and analytical challenges. We identified differences in the frequency and format of data and analysis shared by third-party companies, the assurance activities undertaken by TOCs in relation to these companies, and how this subsequently fed into any changes to processes.

TOCs take different approaches to prosecution

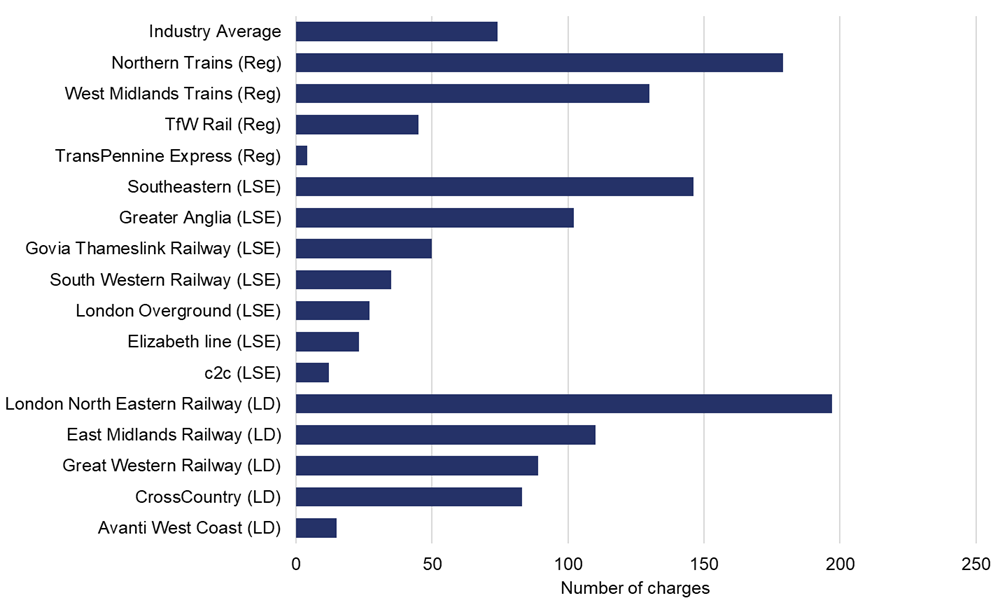

5.107 As shown in Figure 5.1, the volume of prosecutions brought by TOCs varies significantly. The graph normalises the number of charges brought per million passengers travelling, using ORR published data available on our data portal. The variation in prosecutions brought by TOCs is high even after the data is normalised, so the variance cannot be explained by some TOCs carrying more passengers, and therefore there being more journeys that might involve fare evasion.

5.108 The industry average for 2023-24 is for 74 charges brought per million passengers. This ranges from 4 charges per million passengers to 197 charges per million passengers, which highlights the significant variation in TOCs’ approaches to prosecutions. However, it is important to be clear that a higher or lower number of prosecutions does not imply better or worse practice – this would depend on the merits of each prosecution.

Figure 5.1 Total charges brought per million passengers, by TOC, 2023-24

Key: Regional (Reg), London and South East (LSE), Long Distance (LD) and Open Access (OA)

Source: ORR analysis of TOC data. Note: The chart excludes Merseyrail because the way Merseyrail reports charges was not meaningfully comparable to other TOCs. Data was unavailable for Chiltern for 2023-24. Some TOCs run services in more than one sector. The TOCs above have been allocated to sectors based on the sector where trains planned was greatest in 2024-25.

The number of charges and convictions has increased over time

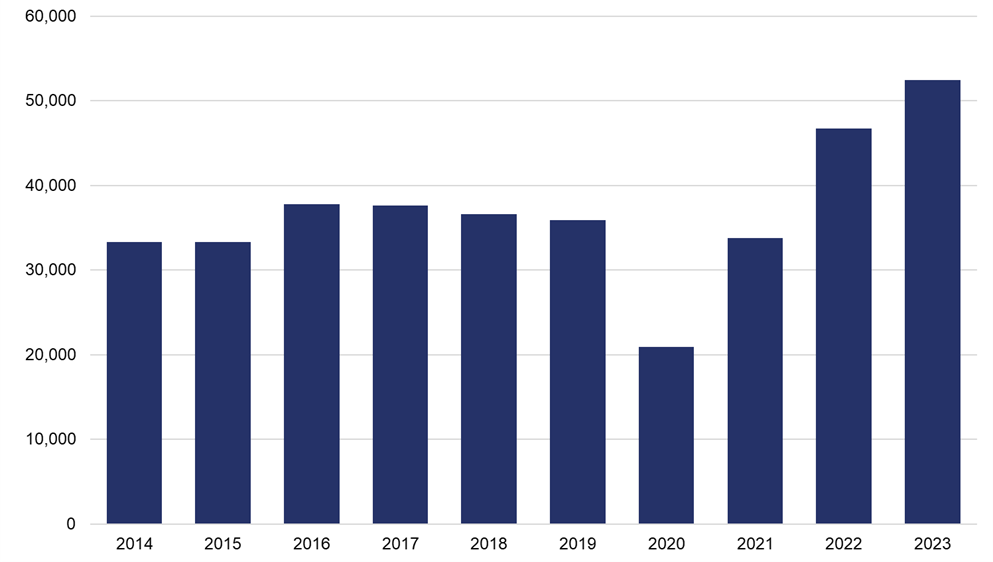

5.109 MoJ published Official Statistics show there has been an increase in the number of charges under Railway Byelaws 2005 in recent years. A further analysis of these byelaw charges shows that the vast majority are for ticketing offences.

5.110 While in part this is reversing a fall in 2020 when both passenger numbers and prosecutions dropped sharply owing to the Covid 19 pandemic, the numbers of charges under Railways Byelaws 2005 in 2023 (the most recent year for which we have data) is 52% higher than in 2019 (the last year before the pandemic). In the same period passenger numbers fell by 7%.

5.111 This suggests an increasing willingness by TOCs to prosecute passengers who do not have the correct ticket for their journey(s), including using the strict liability provisions set out in the railway byelaws (though it may also be influenced by the ability to use the SJP).

Figure 5.2 Charges for ticketing offences under Railway Byelaws 2005

Source: ORR analysis of MoJ published Official Statistics on Railway Byelaws 2005. We have not included charges under RoRA, TfL Byelaws or Merseyrail Byelaws as we cannot disaggregate which of these relate to ticketing offences.

5.112 The data available does not differentiate between those prosecutions carried out under the SJP or using the full Magistrates’ Court procedure, meaning it cannot tell us whether the increase is due to the change in 2016 legislation that allowed TOCs to use the SJP to prosecute passengers.

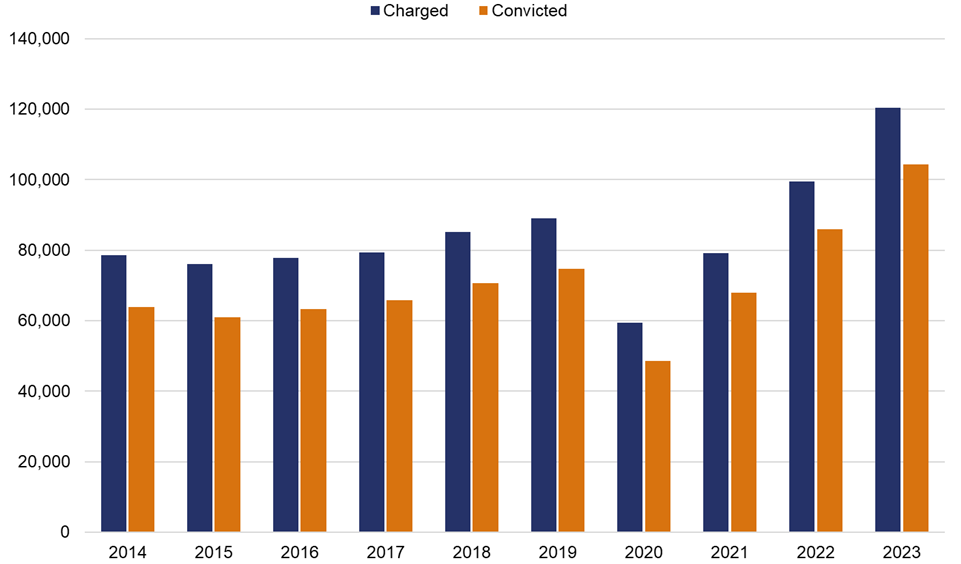

5.113 The MoJ published Official Statistics also suggest that a large proportion of those who had charges brought against them under either RoRA or applicable byelaws were subsequently convicted. This includes those charged for any offence, not just ticketing offences. (Due to the annualised data and the timeframe between a charge and corresponding conviction, MoJ Official Statistics include advice that the data cannot be used to derive a conversion rate between those charged and those convicted in a year.)

5.114 Over time the number of prosecutions and convictions has steadily increased. Since 2014, there has been a 53% increase in the number of charges brought and a 63% increase in the number of convictions, under these legislative provisions.

Figure 5.3 Numbers of people charged and convicted (see note)

Source: ORR analysis of MoJ published Official Statistics. Note: Includes charges and convictions under RoRA, Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Act and the applicable byelaws, 2014 to 2023.

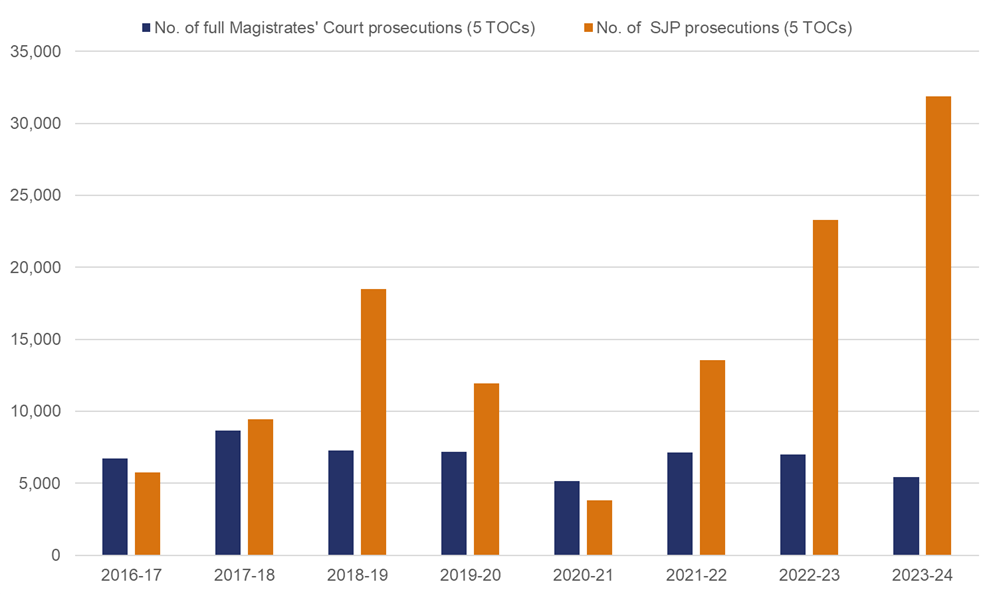

5.115 Based on the data we received from five TOCs who were able to provide complete data on prosecutions for the period 2016-17 to 2023-24, we can see that the increase in prosecutions reflects the increase in SJP prosecutions specifically, while the numbers of non-SJP prosecutions have remained broadly stable over this period (Figure 5.4). However, it is important to note that – given this was only 5 out of 18 TOCs (and one of these accounted for half of the increase) – this chart is indicative rather than conclusive.

Figure 5.4 Number of charges brought through the full Magistrates’ Court and procedure under the SJP for the five TOCs who provided a complete dataset for the period 2016-17 to 2023-24

Source: ORR analysis of TOC data

5.116 Taking into consideration the increased use of the SJP by TOCs, alongside what we have also learnt through industry engagement and the research we have commissioned, other factors which may have contributed to the increase in TOC prosecutions include:

- passenger behaviour change since the Covid-19 pandemic and an increase in the incidence of fare evasion, including in the context of the cost-of-living crisis and increases in other types of crime;

- growth in online purchasing of tickets creating opportunities for TOCs to more easily detect fare evasion;

- greater focus on revenue protection and enforcement among some TOCs and refinements to revenue protection tactics as well as improved counter measures; and

- improvements in TOC processes and technology, streamlining the enforcement process.

Inconsistent data capture and quality

5.117 There is no requirement on TOCs to publish data on their revenue protection enforcement activities. This contrasts with, for example, requirements on local authorities in England and Wales to produce annual reports in relation to environmental or parking enforcement.

5.118 We found that TOCs use a range of different systems to report, collate and analyse revenue protection activities. TOCs use different terminology for similar processes and actions, which in some cases meant their data was not directly comparable. TOCs were, in general, unable to provide complete data on many of the actions they took and the outcomes from the prosecution process. This has limited our analysis of the prosecution process, the outcomes produced and their potential impact on passengers.

5.119 Further, when comparing TOCs’ data on numbers of convictions with MoJ published Official Statistics, we found that MoJ reported 14% more convictions in 2023 under RoRA, Railways Byelaws, TfL Byelaws and Merseyrail Byelaws offences than TOCs included in their responses to us. Possible reasons for this include:

- different reporting periods (MoJ published Official Statistics are by calendar year, TOC data is by rail year running from 1 April to 31 March); and

- reporting choices, for example we know that some TOCs removed from their response any cases which had subsequently been declared null and void following the August 2024 Chief Magistrate’s ruling.

5.120 However, the large variance highlights some of the challenges the industry faces in understanding the scale of TOC prosecutions. It raises a concern that TOCs may not have sufficient oversight over their own processes to provide meaningful assurance of their approach or to support continuous improvement.

5.121 We are not aware of any mandatory requirement to publish data and we found no evidence of the data we requested being published on a regular basis by TOCs or third-party contractors. This limits transparency and makes it difficult to assess the scale and impact of prosecutions.

5.122 Without an agreed dataset or parameters for recording revenue protection prosecutions or their outcomes, it is unsurprising that data is recorded in different ways by different TOCs. The lack of consistent, high-quality data makes it difficult to quantify and assess the impact of revenue protection prosecutions on passengers and industry.

Impact on passengers and industry

How convictions are recorded

5.123 Different offences may be recorded differently. This means that the approach taken by different TOCs, for example which legislation they use, can lead to different impacts depending on the offence of which a passenger is convicted.

5.124 The law defines which offences must be recorded in the Police National Computer (PNC), the primary database used to check and record someone’s criminal record. As an offence punishable by imprisonment, RoRA section 5(3) is a ‘recordable’ offence. If a RoRA section 5(3) offence results in a fine, it is considered ‘spent’ after one year from the date of conviction, assuming no other convictions in that time.

5.125 Most spent convictions do not need to be disclosed to prospective employers. An unspent section 5(3) conviction which resulted in a fine will appear on a Basic, Standard or Enhanced DBS check. Once spent, it will appear on a Standard or Enhanced DBS check for 11 years from the date of conviction. The same applies for fraud convictions resulting in a fine.

5.126 Most fare evasion prosecutions are for non-imprisonable offences such as RoRA section 5(1) and byelaw offences. These are normally considered immediately spent and are not recorded on the PNC. Therefore, a conviction for these offences would not usually appear on any level of DBS check. A RoRA section 5(1) or byelaw conviction may be recorded on the PNC and be disclosed via a DBS check if, during the same proceedings, the offender is convicted of a recordable offence, such as assault.

5.127 All convictions, regardless of whether they are spent, must be disclosed for UK immigration applications. Therefore, any byelaw or RoRA conviction should be disclosed for consideration as part of an application. Such convictions may also need to be disclosed when applying for visas to visit other countries or in the context of certain security clearance or safeguarding assessments.

Passenger perspectives

5.128 Responses to our Call for Evidence highlighted a range of impacts resulting from their prosecution by a TOC. These include:

- stress, mental and physical health impacts: respondents cited stress and anxiety relating to the potential and actual consequences of prosecution and guilt, shame and difficulty sleeping;

- financial impacts: some individuals cited the fines and costs required on conviction, or out-of-court settlement, as placing a strain on their finances. This included those who considered themselves financially vulnerable; and

- loss of confidence in, or reluctance to travel by, rail.

5.129 Over a third of Call for Evidence respondents who were prosecuted or settled to avoid prosecution mentioned fear of the impact of a criminal record. Several respondents also highlighted their perception that a fare evasion conviction had or would affect their job prospects and there is clearly a perception that fare evasion convictions can have a significant impact on passengers’ lives.

5.130 Some respondents cited the nature of their employment as a factor in agreeing to pay an out-of-court settlement, to avoid the potential impacts of a conviction on security clearance or on their ability to practise their profession. One respondent cited impacts on immigration or visa applications.

5.131 Some responses indicated that impacts can be long-lasting. One respondent expressed their “utter horror” at discovering via an DBS check that they had been convicted of a fare evasion offence four years previously, despite believing that they had resolved the matter via a successful penalty fare appeal. Another respondent expressed surprise when a case which she had settled out-of-court two years previously was disclosed as an ‘open investigation’ when checks were carried out on her in the context of an application via the Family Court, and that it remained on her record for over a decade.

5.132 Compared with passengers subject to other outcomes, respondents who were prosecuted (or settled to avoid prosecution) were more likely to say they were treated “very unfairly”, with 73% responding they had been treated so.

5.133 Several Call for Evidence respondents accepted their ticket was not valid but highlighted the large difference between the original fare and what they paid in court fines and costs, or to settle out-of-court. One respondent was ordered to pay £450 following a conviction for being unable to produce her railcard for a £5.10 fare. She subsequently had the conviction overturned after re-opening proceedings. Another respondent settled out-of-court for £100 when he could not produce a valid railcard for a 60p saving on a fare.

5.134 These examples of passengers’ experiences of fare evasion prosecutions may be understood in the context of the Illuminas report (discussed in more detail in chapter 4). In particular, the finding that while passengers agree that penalties are required to deter deliberate fare evaders, there is frustration at what passengers see as severe penalties for ‘minor mistakes’ made in the context of complex rules.

Deterrence, enforceability and industry perspectives

5.135 As noted in chapter 4, revenue protection staff we spoke with often emphasised the importance of educating passengers on the need to buy a ticket and ensuring fare evaders are aware of the potentially serious consequences of their actions. This was also reflected in TOC strategies and policies.

5.136 As noted above, prosecution is used more widely across industry to enforce unpaid fares than civil legal action. Industry stakeholders have told us that, due to the cost of bringing claims in the civil court and long waits for cases to be heard, pursuing unpaid fares via criminal action provides an efficient and cost-effective way of taking enforceable action against fare evaders compared with civil action.

5.137 We understand TOCs use data to target and evaluate the effect of their revenue protection activity and can demonstrate reductions in ticketless travel or increases in ticket sales because of revenue operations. However, it is not clear to what extent these effects are attributable to the impact of actual or prospective prosecution versus other inputs such as visible staff presence, passenger education, increased ticket checking and other actions such as penalty fares.

Financial impact on industry

5.138 In most circumstances fare evasion offences are punishable by a fine. However, when a court in England and Wales passes a sentence it must also order the payment of a ‘victim surcharge’. This varies from £20 to £2,000 depending on factors including the offender’s age and sentence. As well as this and the fine, a person convicted of a fare evasion offence may also be ordered to pay prosecution costs and compensation.

5.139 Court fines are paid via HMCTS and ultimately to HM Treasury central funds. Whereas the victim surcharge is used to fund victim services, and the unpaid fare and prosecution costs are allocated to the TOC.

5.140 MoJ published Official Statistics show that in 2023 the total fines in railway prosecutions were around £21 million. MoJ does not publish data on the value of victim surcharges awarded.

5.141 In terms of revenue and costs awarded to TOCs as a result of prosecutions, MoJ published Official Statistics show the total value of compensation awarded in 2023 was between £2 million to £2.5 million for all offences, of which £1.1 million was for Railway Byelaws 2005 offences.

5.142 For Railway Byelaws 2005 convictions, the average compensation awarded was approximately £25, and less than this in 75% of cases. Robust data was not available to assess the value of costs awarded to industry via fare evasion prosecutions or the revenue and costs recovered via out of-court settlements. This makes it extremely difficult to assess how effective prosecutions are in recovering revenue.

Conclusion on assessing the scale and impact of TOC prosecutions

5.143 It is important that industry has enforceable mechanisms to recover unpaid fares, and prosecution provides one such mechanism. Passenger awareness that individuals are being prosecuted for fare evasion may also discourage other potential fare evaders and give confidence and assurance to fare-paying passengers.

5.144 However, based on the evidence available it is hard to determine the extent to which prosecution itself reduces fare evasion, and we note the varied and potentially significant impact on passengers who are prosecuted – including those who have made honest mistakes. As well as highlighting the importance of a transparent and fair approach to enforcement, there is more work to do to understand the impact of prosecution on fare evasion relative to other revenue protection activities, and its overall costs and benefits.

5.145 This is especially important in the context of the observed increases in TOC prosecutions in recent years. While there are likely to be several reasons for the increase, if recent trends continue then prosecutions will almost certainly be impacting more passengers in the future. This may mean industry is recovering more revenue, to the benefit of the railway.

5.146 However, it also means an increased risk of detrimentally impacting a passenger or cost or reputational damage to industry if things go wrong. It also further underscores the importance of ensuring that industry data and reporting on prosecutions is high quality, consistent and fit for purpose in order to provide a clear picture of the outcomes for both TOCs and passengers.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 5 (‘Greater coordination, oversight and transparency of revenue protection activity’) addresses the need for a shared revenue protection dataset with consistent measures to support long-term oversight and to improve transparency. It also covers promoting best practice across all aspects of revenue protection policy and enforcement, including establishing or improving feedback loops to understand what works best and what drives intended (or unintended) outcomes.