Introduction

4.1 This chapter focuses on our analysis of industry policies and practices around revenue protection. The review’s terms of reference covered this area as follows:

- Revenue protection enforcement practices – the appropriateness of the enforcement approach, and the options available for TOCs to enforce revenue protection.

- Non-compliance with ticketing rules – the classification of ticket non compliance, and how different types of ticket non-compliance should be addressed, considering proportionality and severity.

- Operator assurance and accountability – assessing current assurance and accountability processes that operators have in place, and systems for revenue protection enforcement.

- Communication of enforcement approach – the appropriateness and proportionality of communication with passengers, including at the point of sale, and through enforcement practices e.g. letters.

4.2 This chapter reviews these points, exploring:

- the tools available to TOCs to protect revenue and tackle fare evasion and how TOCs use these depending on their revenue protection policies and operational and commercial constraints;

- the classification and treatment of ticket non-compliance, including the need for an escalated approach to enforcement based on the likely intent of the passenger (i.e. unintentional mistake or intentional fare evasion);

- the information available to passengers regarding the implications of travelling without a valid ticket and whether this is easy to access, clear and accurate; and

- how TOCs, both individually and collectively, assure themselves that revenue protection activity is being carried out consistently, is generating the right outcomes, and is continuously improving to adapt to changing trends in fare evasion.

Revenue protection enforcement practices

Overview of issue

4.3 TOCs have access to a range of options to tackle fare evasion. This includes tools set out in legislation, such as the penalty fares regime, and alternative solutions developed by industry, such as unpaid fare notices (UFNs). Each TOC’s approach (including what tools it chooses to use) will be reflected in its revenue protection policy.

4.4 While a ‘one-size fits all’ approach to revenue protection is unlikely to be appropriate due to differences between TOCs, our analysis shows that the breadth and variety of revenue protection tools employed by TOCs can create significantly inconsistent outcomes for passengers in similar circumstances.

4.5 This inconsistency impacts both the remedial action passengers are asked to take, but also their ability to appeal any action taken against them. Where appeal regimes do exist, the process for appeals and transparency around them varies, further impacting passengers’ experience and their perception of fairness regarding revenue protection.

Findings

The toolkit available for TOCs to implement revenue protection measures

4.6 Over 2023-24, TOCs recorded 876,000 revenue protection actions. This is in the context of 1,612 million passenger journeys across the network in the same period.

4.7 TOCs have a number of different tools at their disposal to implement revenue protection measures.

- Excess fares: if a passenger has a ticket that is partially valid for their journey, they may be required to pay an excess fare. This covers the difference between the original fare paid and the correct fare for a fully valid ticket (e.g. their complete journey).

- Penalty fares: a penalty fare is an exceptional fare that may be charged if a passenger does not comply with the normal ticketing purchase rules without good reason. The passenger must pay a set penalty amount either immediately or within a specific period. In England, the penalty fare is £100 plus the price of the applicable full single fare, reduced to £50 plus the price of the applicable full single fare if paid within 21 days. In Wales, the penalty fare is £20 or double the full single fare (whichever is greater). As discussed in chapter 1, penalty fares are set out in legislation.

- Unpaid fare notices (UFN) or failure to purchase (FTP) notices: some TOCs issue UFN or FTP notices when passengers fail to produce a valid ticket upon inspection. These notices are a formal record that the passenger owes the fare. They require the individual to pay the outstanding amount within a specified time frame, often with an additional administrative fee for late payments. There is no common framework for UFN or FTP notices and TOCs take their own approach to them.

- Irregularity reports (‘IRs’) and notices: a ticket or travel irregularity or incident report (TIR) can be used where a passenger’s ticket is in question, whether due to a technical error, a misunderstanding, a failure to produce the correct ticket, or a more complex fare dispute. Where these have been issued, passengers often receive a copy (a ticket or travel irregularity notice). TIRs provide TOCs with a way to record and resolve the incident, either by allowing the passenger time to rectify the situation or by investigating further if necessary (which can potentially lead to prosecution).

- Yellow cards: a ‘yellow card’ is a formal warning to passengers. If the passenger is found without a valid ticket again within a specified period, they may face harsher penalties or prosecution.

- MG11s: Revenue protection staff may also produce a witness statement (known as an ‘MG11’) to record details of incidents, such as fare evasion, which may be used in legal proceedings. This is discussed in more detail in chapter 5.

- No further action: instead of using one of the above tools, staff may exercise their discretion and decide to take no further action.

Table 4.1 TOC revenue protection enforcement tools grouped by sector

| Approach used | Long Distance (Excl. Open Access) (5) | Long Distance (Open Access) (3) | Regional (6) | London & South East (8) | Number of TOCs (22) per option |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excess fares | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| Failure to purchase notices | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| MG11s produced by frontline staff | 4 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 14 |

| Penalty fares | 2 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 15 |

| Travel irregularity notice / travel irregularity reports / irregularity reports | 5 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 13 |

| Unpaid fare notices | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 16 |

| Yellow Cards | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

Note: ‘Long Distance (excluding Open Access)’ covers those TOCs that are either in public ownership or are contracted by government. The table excludes Heathrow Express and Caledonian Sleeper as they do not use any of these tools.

4.8 These tools are a mixture of:

- tools set out in legislation with clear and defined rules regarding application and clearly defined appeal processes (i.e. penalty fares); and

- practices developed by the rail industry to tackle fare evasion.

4.9 The variety of tools, each with different levels of oversight and transparency, means that passengers in similar circumstances can experience a materially different outcome depending on the tool chosen. Some, such as UFNs or FTP notices do not have common rules or guidance around their use and approaches can vary between TOCs (as noted above). For example, there may be no process for passengers to appeal or dispute the notice.

Factors influencing TOCs’ enforcement approach

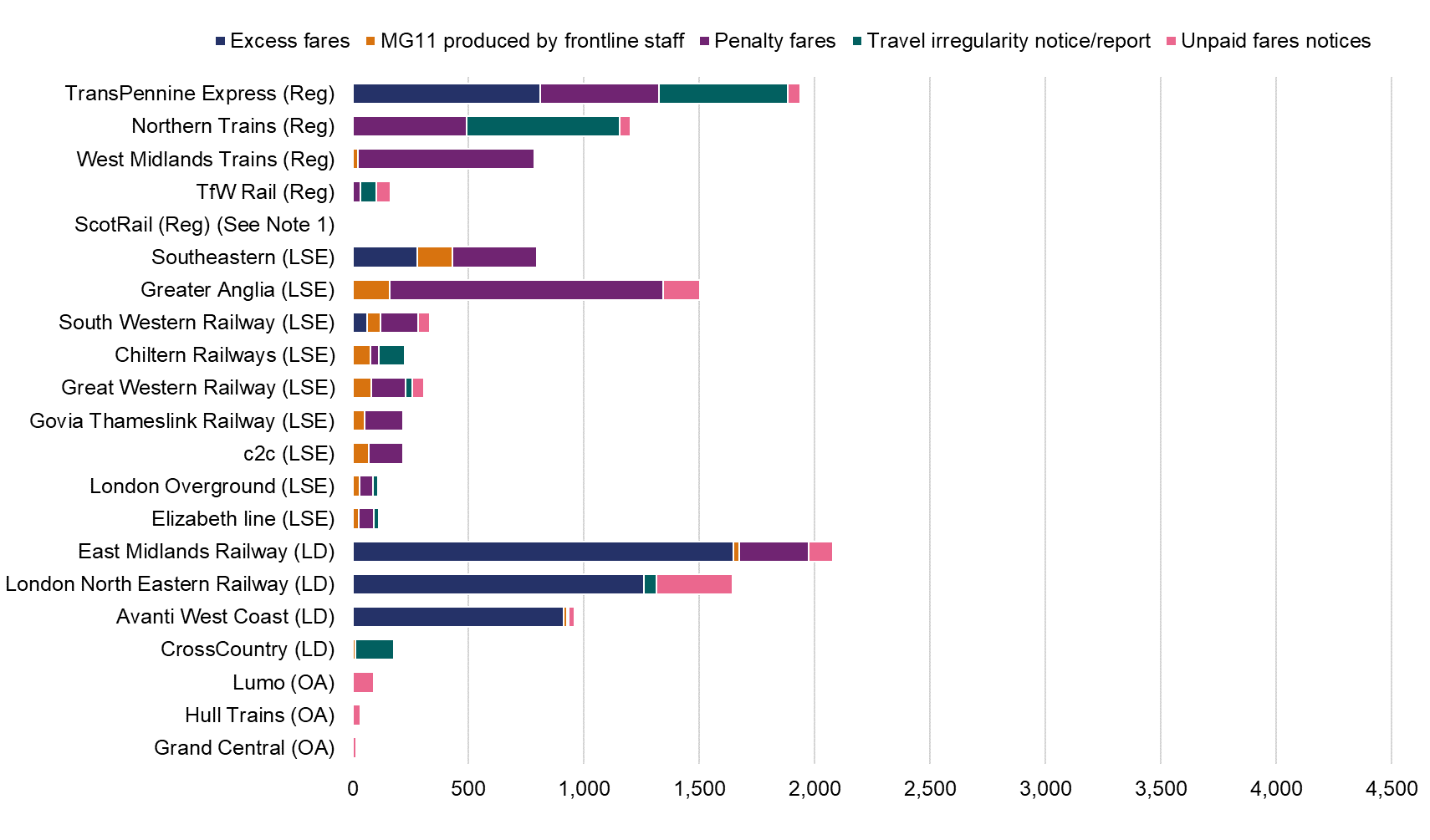

4.10 These tools are used differently by different TOCs, who can choose what action they take. Using TOC data, Figure 4.1 shows the frequency with which various tools are used by TOCs. Penalty fares were the most used option with around 380,000 penalty fares issued in this period. In contrast, more recent innovations such as yellow cards and FTP notices are used much less frequently.

Figure 4.1 Volumes of enforcement actions taken per million passengers, by TOC, 2023-24

Key: Regional (Reg), London and South East (LSE), Long Distance (LD) and Open Access (OA)

Source: ORR Analysis of TOC data.

Note 1: ScotRail’s actions are not visible on the graph’s scale. ScotRail recorded three TIRs per million passengers and two UFNs per million passengers in 2023-24.

Note 2: Merseyrail has been omitted from the chart because the data for some of its enforcement actions is not meaningfully comparable to other TOCs. However, in relation to penalty fares, Merseyrail recorded 705 penalty fares per million passengers in 2023-24.

Note 3: Some TOCs run services in more than one sector. The TOCs above have been allocated to sectors based on the sector where trains planned was greatest in 2024-25 .

4.11 Figure 4.1 should not be read as indicating that greater (or lesser) use of a particular tool is a better or worse approach in itself; we have included the chart merely to demonstrate the scale of different approaches in use and variety of approaches across the industry. The appropriateness of the use of a particular tool will depend on the specific circumstances in which it was deployed and cannot be implied from the chart. In addition, TOCs may take different approaches to how they issue MG11s, so it is important to note that Figure 4.1 does not cover the total number of MG11s issued by TOCs; it only includes MG11s issued by frontline staff (and not those issued later by office-based staff). (Table 5.1 in chapter 5 sets out the total charges brought by TOCs in 2023-24. )

4.12 The use of these different tools by each TOC is determined by its enforcement policy. These policies are tailored to a TOC’s particular operating environment and our analysis has found that a range of factors influence both the content of these policies and how they are operationalised:

- Legislative framework: Chapter 1 set out the legislative framework for revenue protection, including penalty fares. The legislation in place varies by country, with Scotland’s legal system different to that in England and Wales, affecting the options available.

- Commercial context: TOCs have different commercial models and objectives. This drives TOCs to prefer certain revenue protection tools, or to set different thresholds before revenue protection action is taken.

- Ticket gates: The availability of ticket gates at stations across a TOC’s network will also influence its choice of revenue protection tools. Networks with an open station environment (fewer ticket gates and fewer staff) often face a greater incidence, or a different type, of fare evasion relative to more closed networks (more ticket gates and more staff) which are more able to routinely enforce ticket compliance. (ORR has conducted a market study into ticket gate technology and has provided updates on industry progress in this area. Some of the recommendations from that review were aimed at increasing the potential for innovation and the introduction of new approaches to retail and revenue protection.)

- On-train staff: Some train services are operated as “Driver Only Operation” – while others are operated with on-train staff, checking tickets.

- Use of technology: Staff equipped with more sophisticated electronic devices can use these to assess whether a passenger has a history of fare evasion, whether they have electronically validated their ticket, etc. This gives the revenue protection and back-office staff more evidence on which to base their decisions.

4.13 In addition to the broader policies in place within TOCs, our analysis found that passengers’ experience of revenue protection also varies depending on the individual member of staff they interact with within each TOC. A number of factors affect how different staff members approach revenue protection:

- The role / grade of the member of staff: Not all staff have the power to issue penalty fares and they may sell a passenger a ticket or give ‘words of advice’ instead.

Some revenue protection staff informed us that despite their TOC’s policy requiring passengers to buy a ticket before boarding where facilities to do so are available, they were aware that some conductors or guards will sell tickets to passengers who had the means to buy a ticket before boarding. Arguably the conductor or guard should not have done this, as the passenger should have been subject to a revenue protection response instead. Selling tickets in this circumstance is inconsistent with TOC policy and can cause confusion for passengers. It can lead to a misunderstanding by a passenger that it is always acceptable to purchase a ticket on board, and is likely to be perceived as unfair if the passenger is sanctioned for something that previously seemed to be permitted. - Individual staff discretion: Every TOC policy we have reviewed includes some degree of discretion for revenue protection staff on what action to take when they encounter a passenger without a valid ticket. This means that staff must decide on a case-by-case basis whether discretion is suitable to apply. While these decisions will be guided by TOCs’ individual policies, this approach will always be inherently subjective and will lead to different outcomes for different passengers.

- Use of agency staff: TOCs use third party agencies for a range of activities – e.g. providing additional capacity during high passenger volume events. Agency staff will be required to follow established TOC policies but may lack the experience of equivalent TOC staff. The interviews conducted with staff (to inform the Savanta report) highlighted a perception among TOC staff that using externally sourced staff can affect consistency of approach.

4.14 The wide range of policies, tools, and systems in use – combined with the human element of staff interpreting and applying them – will inevitably result in inconsistent outcomes for passengers in similar circumstances. As a result, a passenger’s experience of revenue protection may vary significantly.

Appeals against revenue protection action

4.15 The different tools available also have different processes for appeals. Our review has identified a range of concerns with the approach to appeals.

The penalty fares appeal process

4.16 Penalty fares are provided for through both the Railways Act 1993 and the underlying penalty fare regulations. The current appeal process, which was introduced in 2018, was intended (as the then Rail Minister said at the time) to ensure that those making genuine mistakes would be treated fairly.

4.17 TOCs that issue penalty fares are required to provide an independent appeal service for passengers to use. TOCs currently use one of two companies to deliver the required three-stage appeals process, ‘Appeals Service’ (a trading name of ITAL Group Limited) or Penalty Services Limited. Some TOCs contract with the penalty fares appeals bodies to provide a form of appeals process for other unregulated notices that they issue (i.e. UFNs).

4.18 We saw evidence of appeal bodies focusing on the strict liability aspect of the ticket irregularity, regardless of whether a passenger had made an innocent mistake and the proportionality of the financial impact to the TOC in relation to this.

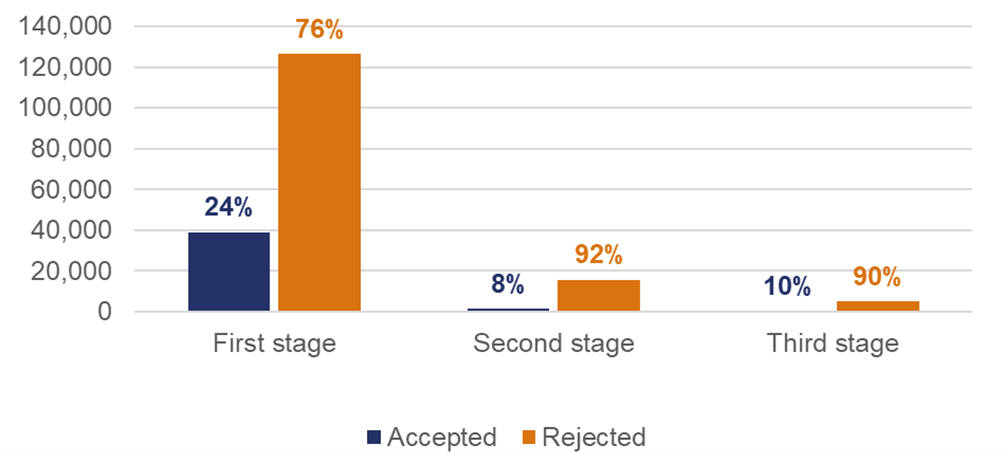

4.19 From the data provided to us by penalty fare appeals companies, the majority of appeals are rejected (as per Figure 4.2 below), and this is consistent across all stages of appeals. This would suggest that the majority of penalty fares are issued in accordance with current rules and processes. However, as we discuss below there are some issues with the process.

4.20 While we note the value of having a wholly independent panel to consider appeals at the third stage, the penalty fares appeals process is relatively long and may deter some passengers from using it. The three-stage process can take up to three months to navigate in full. While other rail bodies also operate a three-stage process (e.g. TfL and Nexus), examples from other sectors, such as council car parking bodies, use a two-stage process.

Figure 4.2 Number of accept / reject decisions at each appeals stage (1 April 2023 to early February 2025)

Source: ORR analysis of data provided by penalty fare appeals bodies.

4.21 If rejected at all three stages and a passenger remains aggrieved, it is open to them to raise the matter with Transport Focus or London TravelWatch, who (subject to their view of the case) may decide to raise it with the TOC in question. Passengers unhappy with the process may also seek to refer a complaint to the Rail Ombudsman. However, they are only permitted to do so after they have exhausted the relevant TOC’s complaints process, which could take up to eight weeks. Furthermore, the Rail Ombudsman’s remit is limited in relation to revenue protection and so (depending on the nature of the issue) the complaint may not be considered within scope (as highlighted in the Rail Ombudsman report).

4.22 Work by Transport Focus has also highlighted issues with the penalty fares appeals process. Its 2020 report made recommendations to improve this. While some recommendations appear to have been actioned (e.g. improved information in letters), others (e.g. public reporting) do not. Like Transport Focus, we found several issues with the appeals process which are common to other aspects of revenue protection such as a lack of oversight, data and reporting, and overall transparency. The lack of data sharing and reporting also seems to limit TOCs’ ability to learn from the appeals process.

4.23 In particular, the industry may wish to note the following when considering potential improvements to the current appeals process.

- As noted earlier, the policy intent of the current appeal process was to ensure robust protections for innocent passengers. Yet there are cases of potentially meritorious appeals being denied and those seeking to appeal can also find the system hard to navigate.

- Submitting a good quality appeal is made more difficult due to frequently asked questions and other upfront material lacking information on the criteria for appeal.

- One of the statutory criteria for appeal is “compelling reasons…in the particular circumstances of the case” that the appeal should be upheld. However, there is no elaboration anywhere of what this means in practice, and in the context of strict liability, it can be interpreted very narrowly. This lack of clarity risks different and inconsistent application by the two penalty fare companies and unfair outcomes for passengers.

- Transport Focus’s 2020 report found cases of appeals where clearly compelling reasons were not accepted and where it had to intervene. We did not find sufficient evidence to assure ourselves that the system has improved since then. The fact that Transport Focus and London TravelWatch continue to intervene on behalf of passengers after an appeal has been denied a third time is indicative of this.

- There is no effective oversight of the penalty fare bodies, nor is there any auditing of their decisions (DfT and Transport Focus were involved in establishing the current processes but do not have an ongoing oversight role in this area). The penalty fare bodies’ accountability is purely to the TOCs who contract with them. Furthermore, only one of the appeal companies publishes any data on outcomes of appeals and there is no reporting on this, meaning transparency is very limited. More oversight and transparency would provide greater assurance on whether the process is working effectively and provide broader accountability.

- There is scope for appeals bodies and TOCs to do more to utilise insights from appeals to support continuous improvement (both in determining appeals and in addressing causal factors).

Appeal processes relevant to other revenue protection tools

4.24 While the penalty fares appeals process is defined in legislation, appeals for other revenue protection tools do not have the same passenger safeguards and so the arrangements can vary on a TOC-by-TOC basis. For example, some TOCs provide an appeals process for UFNs, whether through an appeals body or in house, whereas others do not.

4.25 In some cases, there is no evidence of an appeals process for other revenue protection tools. For example, we could not find an appeals process for FTP notices. As such, a passenger may face difficulties if they feel they have grounds to challenge the notice.

4.26 This inconsistency and lottery in both the availability of appeals processes for different revenue protection actions and in the application of and approach to the appeals processes that do exist further highlights the inconsistent approach to revenue protection across the network.

Conclusions on issue

4.27 The breadth and range of the revenue protection toolkit available to TOCs affords them some flexibility to take what they consider to be the best course of revenue protection action for their operational circumstances. Staff also play an important role in interpreting and implementing these policies. However, the diverse range of enforcement actions used across the network, coupled with the human element of applying these policies to real-world scenarios, creates an inconsistent revenue protection landscape for passengers and increases the risk of unfair or disproportionate treatment of some passengers, who may appear to be in similar circumstances.

4.28 Passengers should be able to expect fairness in the treatment and outcome from travelling without a valid ticket, whether this is intentional or not. However, as shown in Figure 4.1, passengers without a valid ticket are likely to receive a different outcome depending on TOC they use. This has a material outcome on:

- the penalties passengers receive; and

- their ability to appeal against any action taken.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 2 (‘Strengthen consistency in how passengers are treated when ticket issues arise’) addresses this issue in the main, proposing consistent principles and a governance framework for revenue protection for all TOCs.

- Recommendation 4 (‘Make information on revenue protection easy to access and understand’) covers the need to clarify the ‘compelling reasons’ criterion for penalty fare appeals, as well as providing better and easier access to information on the process for appeals.

Classification and treatment of ticket non-compliance

Overview of issue

4.29 A primary concern of this review is to consider how ticketing non-compliance is classified and how it should be dealt with. As we noted earlier, there is currently an inconsistent approach to this – largely because of variation in legislation, TOC policy and differences in how staff deal with individual cases.

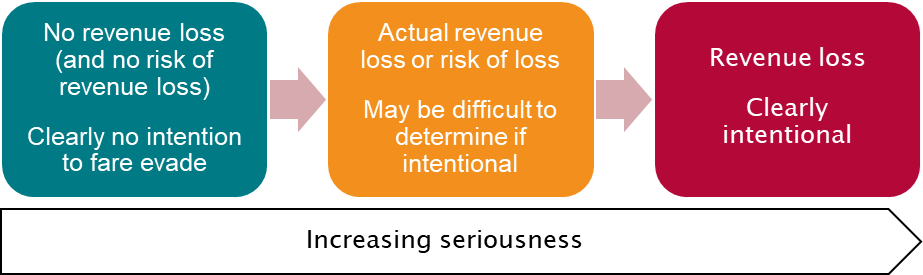

4.30 In this section, we consider different types of ticket irregularity and how these should be addressed. We have not sought to comprehensively identify each particular invalidity. However, we have identified three broad categories of ticket irregularity based on the intent of the passenger and whether there is any revenue loss, as set out in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Broad categories of ticket irregularity

Findings

Ticket irregularities involving no revenue loss and no risk of revenue loss

4.31 Where there is a ticket irregularity that involves no revenue loss (and there is no risk of revenue loss) then there is unlikely to be any material harm, commercial or otherwise, to a TOC. An example might be travelling with a ticket with the wrong railcard discount applied, but one with the same or a lower level of discount to the railcard held by the passenger.

4.32 Our Call for Evidence received a submission from a passenger with this type of irregularity who was threatened with prosecution but given the opportunity to settle out of court for £150. They also provided supporting evidence to substantiate their account.

4.33 In the case mentioned above, which was clearly a genuine error, the primary intent of TOC action appeared to be either enforcing strict liability to the letter or increasing revenue collection, even when it was seemingly unfair and disproportionate relative to the circumstances. This raises questions about the intent and implementation of the TOC’s overall high-level strategy and its operational objectives for its revenue protection activities, as well as its staff’s understanding of this and the TOC’s oversight of what its staff were doing in its name.

4.34 We can see no reasonable justification for penalising passengers where no revenue has been lost and where there is no risk of loss. In our view, TOCs should urgently clarify their policies to ensure no penalisation can occur in such cases. To underpin this, the NRCoT could then be amended to formalise this in the T&Cs.

Ticket irregularities where there is revenue loss (or a risk of revenue loss) but where it may be difficult to determine the true intention of the passenger

4.35 The more complicated scenario is a ticket irregularity that involves revenue loss to a TOC (or a risk of revenue loss) but where it is difficult to determine whether the passenger acted intentionally. For example, a passenger who bought their ticket online says that they were unable to (or did not realise they needed to) collect their ticket from a TVM before departure.

4.36 Here, the passenger may have acted honestly and be able to (later) prove that they purchased a ticket (for example, with a credit card or ticket receipt or with an email showing the purchase). However, this irregularity involves the potential for revenue loss, and we understand that this is a common scenario that revenue protection staff must deal with. We do not describe the specifics of this revenue loss risk for TOCs here for reasons of commercial sensitivity. Nevertheless, the broad point is that technicalities exist that some passengers may seek to exploit and the challenge for rail staff is to ascertain the passenger’s intent and to respond appropriately.

4.37 For this reason, an honest passenger being able to prove later that they did purchase a ticket may not be sufficient to avoid a sanction. A similar risk applies with an e-ticket that a passenger says they are unable to present because of a flat battery on their phone or device. The result is that an honest passenger may find themselves being penalised in this situation.

Case study (Call for Evidence): A passenger was normally given e-tickets by his work for business travel: However, on this occasion they were booked a ticket that needed collecting from a TVM. The passenger did not realise and, thinking they had an e-ticket as usual, travelled without the printed ticket. The passenger appealed the penalty fare at all three stages, but this was rejected.

Although it was an innocent mistake and the ticket was purchased (meaning no loss to the industry), the passenger was in breach of the T&Cs and had received an email which clearly stated they must collect the ticket.

4.38 Another scenario is where a passenger claims a railcard discount to which they are not entitled but where it is possible for honest passengers to make a genuine mistake. A simple example is selecting the wrong railcard. A passenger might have a plausible case for how they made a mistake, but they are still in breach of the rules. As such, TOCs are within their rights to penalise them.

4.39 We also gave real-life examples in chapter 1 where mistakes had been made regarding railcard T&Cs. In one case, the discrepancy (revenue loss) was as low as £1.60 and the passenger was prosecuted. This highlights the issue of proportionality. That is, is it fair to penalise a passenger many times the level of the discrepancy in price that they should have paid, or to prosecute them for a minor violation, particularly where the passenger may have made an honest mistake.

4.40 We know from our conversations with industry stakeholders that some intentional fare evaders persistently use the same technique to save relatively small amounts of money each time they travel. In such cases where there is evidence of repeat behaviour, a penalty that reflects the overall revenue loss from multiple journeys seems reasonable.

4.41 The challenge is being able to distinguish the deliberate from the unintentional.

Ticket irregularities which are clearly intentional and involve revenue loss

4.42 Where it is clear that a passenger has intentionally travelled without a valid ticket in order to avoid paying the correct fare, there would be fair grounds for penalising them. We return to this later on.

Determining intent

4.43 In addition to the skill and experience of revenue protection staff in assessing whether a passenger with a ticket irregularity has acted intentionally, technology can help to indicate intent and is becoming increasingly important. For example, electronic devices can enable staff to see a person’s recent contactless activity and whether they have a track record of validating their ticket. This can help staff recognise genuine mistakes (such as a failed or forgotten ‘tap-in’) and respond more proportionately (for example, letting the passenger pay the correct fare and taking no further action). We observed this for ourselves when shadowing rail staff.

4.44 Evidence of prior behaviour can also play an important role in determining intent. Some TOCs log a passenger’s details and the nature of their ticket irregularity (along with any action taken). Knowing whether a passenger has made a similar ‘mistake’ before can help inform a response to a further irregularity. If a passenger has previously been shown discretion for a ticket irregularity but has subsequently been found to have committed the same error soon after, then it could point to intent and warrant formal action. The same is true for a passenger with no prior record, where a clean slate may suggest that a ticket irregularity is a genuine error and lend itself to a more lenient course of action.

4.45 But even if a passenger has been judged not to have acted deliberately, under the strict liability regime they may still be penalised

4.46 In the above case, if the staff member recognised there was no intent, they could have allowed the passenger to pay the excess fare rather than penalising them (and potentially recorded the incident, so if there are repeat cases the passenger might not be given the benefit of the doubt). That would have addressed the revenue loss to the TOC from the mistake. It is hard to see any objective benefit in penalising the passenger beyond this, unless the staff member remained unconvinced that it was a mistake, or the staff member felt they simply were enforcing the TOC’s policy.

4.47 We revisit the issue of how ticket irregularities involving actual or potential revenue loss could be better dealt with later in this chapter.

Alternative responses to ticket irregularities – education and behaviour change

4.48 Our analysis suggested that 12 TOCs focused on ‘educating passengers’ in their revenue protection policy. During our review, in conversations with TOCs about improving revenue protection processes, we noted an increasing focus on the need to use education to drive behaviour change – both for passengers making mistakes and those deliberately travelling without a valid ticket.

4.49 While ‘education’ can include things such as posters and announcements, it can be much more proactive. For example, we understand some TOCs use targeted social media campaigns and arrangements with schools to educate young people on the consequences of fare evasion to reduce the likelihood of them doing it. Education to drive behaviour change can also be used as a response to a passenger being found with an invalid ticket.

4.50 It was clear from the revenue protection staff we spoke to that they view educating passengers and supporting behavioural change as an important part of their role. This applies to passengers who have made an innocent mistake and those who have acted intentionally. In both cases, we saw staff use education along with discretion – for example, allowing a passenger to pay the excess fare (rather than issuing any penalty or other notice).

Case study (ORR site visit shadowing revenue protection staff): A 17-year-old was found travelling with a child ticket. The revenue protection officer explained the child ticket age limit was 15. He let the person pay the excess fare but explained why it was important to travel with a valid ticket (including the potential consequences if they were caught again). He also advised that a 16-17 Railcard would allow them to obtain a 50% discount (and effectively pay the child ticket rate).

4.51 Some TOCs also view the use of penalty fares and other notices as part of an educational process when issued alongside advice. For passengers who have made a genuine mistake, there is also value in using the interaction as a learning opportunity in making them more aware of ticket types and restrictions and thus help them make more informed decisions when making future purchases. Though, as we note later, for genuine mistakes, they are likely to be frustrated if they are penalised.

4.52 Professor Christopher Hodges, chair of our Expert Advisory Group, provided advice to us on the use of behavioural techniques. He advised that differentiating between those making unintentional mistakes and those acting deliberately was a fundamental element in operating a fair and just revenue protection policy. It can also gain the support and trust from those who make genuine mistakes if they feel they have been treated reasonably. Some principles and considerations around positive behaviour change he outlined included:

- empowering passengers by more routinely or actively informing them about how to comply with ticket regulations and facilitating this. Industry should be seen to be attempting to help passengers comply by giving them the right information at the right time, and providing quick, easy access to the tickets they need for their journey. It can counter a feeling by some passengers that the system is working against them; and

- promoting a culture of compliance by emphasising the benefits and risks of getting it right or wrong. In a context where some passengers may not consider travelling with an invalid ticket to be a serious matter, they can be motivated to ensure they take adequate time and care if they are more fully aware of the potential risks of getting it wrong (e.g. having to pay more than original due fare, penalties, prosecution). It can serve to create a system where people value doing the right thing.

The strict liability framework

Passengers’ perspectives on fairness and strict liability

4.53 Section 6 of the Illuminas report looks at passengers’ views on liability and penalties. This notes there is a widespread expectation that, provided the passenger has behaved ‘reasonably’ and without any intent to evade the fare, they will be treated ‘fairly’ by the railway. This passenger expectation runs counter to how the strict liability framework currently operates.

4.54 The Illuminas work found that while, initially, most honest passengers accept the railway’s definition of liability in the binary sense that a ticket is valid or invalid, when the implications of this are unpacked, the position is less clear cut. For example, while penalising (deliberate) fare evasion is seen as reasonable, the consensus from passengers is that it is not appropriate that an invalid ticket bought in good faith can be punished through prosecution.

4.55 It also found widespread frustration from passengers regarding being penalised for ‘minor mistakes’ and the disproportionality of the penalties. There was also dissatisfaction with the inconsistency in the system and its scope for causing confusion (e.g. where something is permitted on one occasion or by a particular TOC, but not on another occasion, particularly when it relates to a genuine mistake). This all links back to the risk noted above that the current arrangements may create a situation where passengers feel like the system is working against them.

The strict liability regime in context

4.56 We have looked into the history of the strict liability regime in relation to ticket validity (i.e. byelaw 18). While strict liability in railway byelaws has likely existed in some form for well over 50 years, the wording of byelaw 18 appears to date from the late 1990s when a new generation of byelaws were introduced (for each TOC), superseding pre-privatisation era byelaws.

4.57 This means the current form of strict liability dates from a time when people bought tickets directly from a member of staff (e.g. at a booking office) and when the ticketing system was simpler than it is today. Back then, it would have been harder to make a mistake and travel without a valid ticket. If you were travelling without a valid ticket, it was much more likely that you would be doing so deliberately.

4.58 Now, around 60% of tickets are bought online or via a TVM, without a member of staff to provide assistance (Source: Table 10, Ticket purchasing behaviour and preferences among rail passengers, Department for Transport. Research carried out in February and March 2023). The complexity in ticketing (T&Cs and validity restrictions), as well as weaknesses in retailers’ provision of key information to consumers, mean the scope for passenger error is much greater than it was when the wording of byelaw 18 was first introduced.

4.59 Given this, and the evidence that passengers do make innocent mistakes, there is a strong case to say that byelaw 18 was not designed for the context in which it is now being used. And furthermore, that its use can lead to unfair outcomes.

4.60 On the other hand, we know that TOCs find byelaw 18 of value in dealing with fare evasion – particularly for cases involving a persistent fare evader but where a successful prosecution under RoRA is not practical because of limitations in that legislation.

4.61 Taking both the passenger and industry positions into account, we consider that byelaw 18 should be reviewed to incorporate some sort of reasonableness test to provide appropriate safeguards for passengers making a mistake. Alternatively, or until this can happen, there need to be safeguards built into revenue protection policies and processes to ensure that byelaw 18 and strict liability is used proportionately and appropriately.

Case study: Use of byelaw prosecutions for repeat incidents only

4.62 We are aware of one TOC operating a policy of only pursuing byelaw prosecutions if there is a track record of a passenger travelling without a valid ticket. Its approach is to issue penalty fares for the first two incidents (i.e. where discretion is not appropriate). Where there is a third incident within a year, the TOC will undertake a byelaw prosecution.

4.63 This approach makes it very unlikely that a passenger will be faced with prosecution for a one-off honest mistake, while still providing for persistent evasion to be addressed.

Case study: Strict liability on the Swiss railway (SBB)

4.64 Like in Great Britain, the Swiss railway operates a strict liability regime in relation to ticketing, both in relation to its T&Cs and with the potential for criminal prosecution. It also has a mostly ‘open’ network without ticket gates (and so faces similar challenges regarding fare evasion), with multiple train operators. One difference, however, is that Switzerland has a simpler ticketing system.

4.65 All passengers are required to buy a valid ticket before boarding. If rail staff encounter someone without a valid ticket, they are given a ‘travel without a valid ticket’ document. The same applies to partially valid tickets. They are then later required to pay a surcharge in addition to the fare (similar to a penalty fare). A passenger can appeal later. For example, cases involving no loss of revenue are not penalised. And, if a passenger was unable to present their ticket at the time of being checked but can produce it later, their appeal is upheld and they are not penalised (though they may need to pay a small admin fee).

4.66 There is an escalating system of surcharges, depending on whether it is a repeat incident and whether the passenger had no ticket or a partially valid ticket.

Table 4.2 SBB surcharges for not carrying a valid ticket (excludes cost of ticket)

Circumstance Swiss Francs ₣ (£ equivalent) | First incident | Second incident | Third and subsequent incidents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Travel without valid ticket | ₣90 (£81) | ₣130 (£117) | ₣160 (£143) |

| Travel with a partially valid ticket | ₣70 (£63) | ₣110 (£99) | ₣140 (£125) |

Source: SBB website. (Conversion carried out on 14 May 2025 when ₣1 = £0.90). Note: Incidentally, there are also other charges transparently set out on SBB’s website, including for payment reminders, legal proceedings, debt collection and research to find a person’s address.

4.67 Underpinning this escalatory system is a centralised database to record incidents where a passenger does not have a valid ticket. This is available to all Swiss TOCs. This enables repeat cases to be identified. Data is retained for at least two years. However, a record is deleted if there is a successful appeal or for irregularities where there was no risk of revenue loss. The database has no wider role and cannot be viewed by third parties.

4.68 Criminal prosecution remains a possibility depending on the circumstances. For example, SBB says it prosecutes forgery cases in addition to levying a ₣200 surcharge. But it is not used to leverage settlements or pursue unpaid fares. Civil debt collection is used instead.

4.69 Overall, this is an interesting example of a system that seeks to balance the need to guard against fare evasion, while equally ensuring fairness to the passenger. For example, as well as escalating surcharges, the law allows for surcharges to be waived if passengers proactively approach staff on the train to declare that they do not have a valid (or validated) ticket. It also focuses the use of criminal law on the more serious cases (e.g. persistent evasion).

4.70 However, it is important to note that, with a simpler ticketing system, the likelihood of passengers making honest mistakes as a result of confusion will be much lower than in Great Britain.

Key principles for moderating the use of strict liability

4.71 There will never be a perfect system that ensures fare evaders and innocent passengers are always accurately identified. There will therefore be an element of risk that the revenue protection response to a passenger is not always appropriate to the circumstance (being either too lenient if it was intentional evasion or too harsh if it was a mistake).

4.72 The question is – how should this risk be managed and who should bear the risk. At the moment, the risk lies squarely with the passenger – the framework allows for them to be treated as though they acted intentionally even if they did not. The challenge is to calibrate the system so that it balances fairness while providing for persistent evasion to be addressed robustly.

4.73 If a simplified ticketing system could be established, then a system like that in Switzerland might be adopted. For example, clear upfront rules and escalating penalty fares for any infringements, with the right to appeal. However, it is unlikely that comprehensive fares and ticketing reform will be delivered for some years and, as such, discretion by frontline staff will remain important.

4.74 Reflecting this, a fairer system could be adopted in Great Britain which could provide for discretion (as now, but applied more consistently) along with a more structured way for passengers to be given the benefit of the doubt where an apparent mistake has been made.

4.75 Based on the points made earlier in this section, we think there are some key principles relevant to this.

- Benefit of the doubt:

- The problem with applying discretion and giving the benefit of the doubt (or not giving it) is that it risks inconsistency of treatment for a passenger. For the TOC, it also risks a persistent evader being let off.

- The question of whether the passenger has made a similar mistake before is therefore crucial. In order to know this, there would need to be a way of checking and so a structured approach to logging ticket irregularities and a system for recording these seems essential.

- Escalation: An escalatory approach where initial cases of ticket irregularities can be treated more leniently, while subsequent incidents meet a stronger response, would help to balance risk more fairly between honest passengers making mistakes and TOCs losing out through deliberate evasion. It is also consistent with supporting behavioural change through educating passengers both on how the system works and the risks of not carrying a valid ticket.

- Proportionality: Proportionality is key to fairness, both in terms of the circumstances of a ticket irregularity and in terms of how it should be addressed.

- Passengers who have clearly attempted to ‘do the right thing’ should be given credit for this – e.g. where they have bought a plausible ticket or can evidence that they have purchased one. Logging the irregularity should provide assurance to the TOC that persistent fare evaders cannot ‘game’ the system. It also gives well-meaning passengers the opportunity to learn from the experience and potentially avoid a repeat scenario in future. Where there are repeat cases of irregularities, there would be justification for the TOC to take a tougher approach.

- Furthermore, where the revenue at stake is very low, penalising the passenger disproportionately for a technical error is likely to be unfair (and inefficient) unless they have a history of similar offences.

- If it is clear there is no intent, there is no purpose in penalising the passenger. However, it is fair that the passenger should make good their mistake in terms of paying an excess fare. Though, noting that some ‘on the day’ fares can be very expensive in relation to the price of an invalid ticket, how this works in certain circumstances might need further thought.

- Some ticket irregularities will still warrant a sanction for a first offence depending on the circumstances (e.g. a mature adult with child ticket, unless there are exceptionally good reasons to explain this).

- For initial cases of a passenger having a ticket irregularity, prosecuting (or notifying of impending prosecution) under the byelaws is likely to be wholly disproportionate unless there are aggravating circumstances (e.g. refusal to pay an outstanding fare or penalty fare, evidence that they tailgated or altered their ticket etc.).

Potential escalatory approach to dealing with ticket irregularities

4.76 Based on the above, we have done some initial work to look at how a potential escalatory approach could work. It is important to be clear that this is indicative; it would be for industry and government to consider and develop how such an approach might work in practice, though they could build on this initial model. The indicative approach is explained below and is shown in Figure E1 in Annex E.

4.77 It is based on having a system for recording ticket irregularities where they arise (as some TOCs do already). This would allow a TOC to give a passenger the benefit of the doubt for ‘one-off’ mistakes, such as those who commit a ticket irregularity but have no prior record of infringements, giving staff more assurance that they are not being ‘played’ by a persistent fare evader. Equally, a record of prior infringement would indicate likely intent. Such a system would therefore benefit both honest passengers and TOCs.

4.78 While such an approach could initially be operated by TOCs themselves, there would be benefits in a nationwide system (as in Switzerland). A national system has the potential to strengthen revenue protection activity and support a whole industry approach to tackling persistent fare evasion.

4.79 The system would need to comply with data protection legislation. However, we are aware that the legislation permits data to be collected and shared appropriately in connection with the prevention or detection of crime. While the details of how this might work would need to be considered further, a decision would need to be made on how long data should be retained for – e.g. a set number of years since the previous ticket irregularity.

4.80 The period would need to be long enough to prevent persistent evaders from gaming the system, but not so unduly long that, for example, a reformed former teenage fare evader is prosecuted in later life for an honest mistake. Proportionality is therefore also important in how this operates.

4.81 We are also aware from discussions with industry that the job roles of staff can play a role in who can record information and the types of processes and systems they are required to use. We therefore also acknowledge this is another aspect of implementation that would need to be considered.

4.82 Under our indicative approach, a TOC’s response would correspond to a passenger’s likely intent, with greater scope for giving the benefit of the doubt for ‘one-off’ incidents.

- Where revenue protection staff are satisfied that an irregularity is clearly a mistake, this would not need to be logged. Instead, they could show discretion and explain to the passenger their error. There would only need to be a financial remedy if there would be revenue loss – in which case, an excess fare may be appropriate. Examples might include clicking a 16-25 Railcard instead of a 26-30 Railcard (no excess fare needed), or inadvertently travelling beyond the Oyster card boundary with an Oyster card and approaching staff after not being able to tap out at the gateline (here an excess fare is likely to be appropriate).

- Where intent is uncertain, but the irregularity is quite plausibly a mistake, the revenue protection response could give the passenger the benefit of the doubt. However, any revenue loss would need to be remedied through an excess fare and the incident would be recorded, as a protection against intentional evaders.

- For incidents where it is more likely that the irregularity was deliberate (but where this may not be entirely certain), the appropriate course of action may be a penalty fare (or another appropriate alternative). The incident would be recorded. The passenger would have the right of appeal.

- Passengers would not be subject to a byelaw 18 prosecution unless they have at least three ticket irregularities on record and it was in the public interest to prosecute. Alternatively, if the TOC was able to show that the passenger clearly intended to fare evade, this ‘three strikes’ rule would not apply, and they could be prosecuted under RoRA.

- Potentially, this arrangement could also be combined with an escalating set of penalty fares, so that repeat cases are treated more severely, like in Switzerland. This may give TOCs more scope to resort to prosecution only in particularly persistent cases.

4.83 The existence of a database of ticket irregularities may also provide for the penalty fare appeal process to be made fairer too. Currently, the strict liability approach tends to be reflected in appeal decisions, where appeals made on the basis of a genuine mistake tend to be rejected. In considering whether there are ‘compelling reasons’ why a passenger should not pay a penalty fare, the panel could take account of whether a person has a previous record of ticket irregularities when deciding whether to give them the benefit of the doubt.

Overall objectives of revenue protection and measuring ‘success’

4.84 As part of rebalancing fairness of the revenue protection approach, it would be helpful for there to be a clear overall high-level statement of objectives for revenue protection that apply to the industry overall, approved by or set by government. This could provide top-level clarity for TOCs and their staff so that expectations for how the system should work are clear.

4.85 Alongside this, it would be important that the industry has a way to measure the success of revenue protection in a way that does not focus solely on revenue generation and recovery. It would be for the industry to consider these, but other potential success measures might include (among other things):

- reduction in aggregate fare evasion rates;

- reduction in the number of cases of ticket irregularities that are made through ‘genuine’ mistakes and the number of repeat cases; and

- increasing rates of ticket scanning and validation as a way to help address a significant portion of fraudulent activity. This would also contribute to behaviour change by reinforcing a culture of compliance.

4.86 This would require better data collection and consistent metrics (linked to our findings elsewhere in this chapter) but would underpin a more balanced overall approach and a focus on continuous improvement. It should also support better outcomes for both TOCs and for passengers.

Conclusion on classification and treatment of ticket non-compliance

4.87 While the way that the industry deals with ticketing non-compliance currently provides for a robust approach to fare evasion where genuine fare evaders are caught, it also leads, in some cases, to unfair and disproportionate outcomes for passengers who have made innocent mistakes. The industry should look to rebalance how this works by adopting a more escalatory approach with adequate safeguards that provides greater scope to give the benefit of the doubt to passengers without yielding any ground to persistent fare evaders. This would moderate the strict liability framework to support greater fairness.

4.88 However, as an immediate step, TOCs should urgently clarify their policies to ensure that ticket irregularities involving no revenue loss and no risk of revenue loss are not penalised.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

Recommendation 2 (‘Strengthen consistency in how passengers are treated when ticket issues arise’) covers this issue, including the need to develop and adopt an escalatory approach for dealing with ticket irregularities.

Communication with passengers

Overview of issue

4.89 In addition to ensuring that passengers understand the T&Cs of the tickets that they are purchasing, it is important that passengers also understand the implications of travelling without a ticket and are fully informed of the action being taken against them if they are subject to revenue protection action.

4.90 Our review has highlighted that information about revenue protection is not always clear or provided in a timely manner. This means that passengers do not fully understand the implications of travelling without a ticket and are not informed of the actions they can take to appeal or resolve issues when they are subject to revenue protection action.

Findings

Availability of information regarding revenue protection – TOCs and TPRs

4.91 All TOCs owned or contracted by government (with the exception of Caledonian Sleeper, where passengers can only buy a ticket with a seat reservation for specific services before travel meaning revenue protection is not necessary) have a revenue protection policy, or web page setting out their processes. In contrast, just one open access TOC has a webpage on revenue protection, with others only having generic references within broader T&Cs.

4.92 The overall content, tone and intent of policies differ. Many of those that operate a penalty fare process take a relatively formal approach, delivered through policy documents. However, some take a more customer-centric approach in order to help passengers minimise the risk of getting a penalty fare, delivered through a ‘frequently asked questions’ (FAQ) style format.

4.93 Nearly all TOCs make it clear in their policy that travelling without a valid ticket can result in a criminal sanction. However, not all TOCs set out the circumstances in which the TOC is likely to prosecute (more information about this is set out in chapter 5).

4.94 Our review of information on websites also found that TPRs had little to no information about revenue protection or the consequences of travelling with an invalid ticket on their websites or apps. Where this information is provided, it is often found in small sections of the T&Cs and does not generally have its own web page. While TPRs do not operate train services and, as such do not enforce revenue protection, they account for a large proportion of online ticket sales. This means that if passengers are purchasing tickets through a TPR, they may not be aware of the importance or consequences of travelling with an invalid ticket before they travel.

4.95 Overall, our review suggests that the provision of information could be improved in two ways. Firstly, making relevant information available at a single-source on the TOC’s or TPR’s website or app with a focus on clear and concise drafting that can be understood easily by passengers. Secondly, there is also an opportunity for the industry to develop more high-quality generic information, drafted clearly and concisely, that can be broadly adopted.

Availability of information regarding revenue protection – wider industry

4.96 In addition to information published on TOC websites, the consequences of travelling without a ticket are also set out in wider industry documents. For example, the NRCoT and National Rail Penalty Fare Guidelines.

4.97 These documents should serve as the single source of the truth for passengers and industry regarding revenue protection. However, we found several issues with these documents in terms of lack of cross-referencing, duplication, and important omissions. Omissions include:

- the NRCoT only refers to penalty fares notices and does not refer to other types of notice in use by the industry (e.g. UFNs); and

- neither the NRCoT nor the Penalty Fare Guidelines refer to the penalty fare grounds for appeal.

Information regarding revenue protection action taken

4.98 The information that passengers should receive when revenue protection action is taken varies depending on the type of action taken. A penalty fare notice must include a certain set of information and a copy is given to the passenger. However, the rules around other types of notice can vary by TOC.

4.99 In respect of penalty fares and prosecutions, there are a number of required touchpoints for passengers set out in the 2018 Regulations:

- where passengers appeal a penalty fare, the appeals communication is managed by the appeals body. For example, the appeals body will send a letter to the passenger detailing the outcome of the appeal;

- if a passenger has not paid a penalty fare (or other notice) and not appealed, the TOC will write to them to chase the payment; and

- the TOC will write to a passenger to notify them where a prosecution is being pursued – more detail on this is set out in chapter 5.

4.100 Our analysis indicates TOCs provide what is likely to be the necessary minimum information in these communications. Letters are generally direct and reflect the legal context and requirements – for example, citing the relevant legislation and noting that intending to travel without a valid ticket may constitute a criminal offence and warn of potential outcomes such as prosecution. A small number of respondents to our Call for Evidence considered the letters they received as legalistic and aggressive, especially where they had simply made a mistake with their ticket.

4.101 A small number of responses to our Call for Evidence cited more exceptional experiences including: missing communications (caused by post or emails not arriving, passengers moving house, etc.); identity (fare evaders giving another person’s name and address – also recognised by the Savanta and Ombudsman reports) and privacy (concerns about being interviewed under caution and handing over their confidential contact details on a busy train). One passenger suffered very serious consequences from having their details taken down and subsequently used by a nearby member of public while giving them to a member of staff.

4.102 Transport Focus raised concerns about both the quality and quantity level of information provided in appeals letters in its February 2020 report: Penalty Fares: the appeals process. Case studies from our Call for Evidence indicated that decision letters do include information on why an appeal has been rejected, and what factors were relevant (although other recommendations from that report have not been followed up).

Conclusions on passenger communication

4.103 There are clear areas for improvement for TOCs and ticket retailers in both what information is provided to passengers, and in how accessible and useful it is. Where information is available, it is often provided across different webpages and apps, and can be legalistic in nature, affecting passengers’ ability to understand the implications of travelling without a ticket, or how to appeal revenue protection action. There is also an opportunity for the industry to develop more high-quality single source information, drafted clearly and concisely, that can be broadly adopted (including, for example, passenger correspondence templates).

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 4 (‘Make information on revenue protection easy to access and understand’) covers this issue.

Operator assurance and accountability

Overview of issue

4.104 In line with the terms of reference, we have assessed the ways in which TOCs assure themselves that the revenue protection policies they have adopted are being implemented as intended. We looked at how staff are held accountable for delivery and examined how these policies, including any underlying processes and systems they rely on, are reviewed and improved over time.

4.105 We found that the industry is largely self-assessing and self-assuring revenue protection performance in this respect. TOCs set their own policies and are not required to report externally on their activities. Passenger service contracts require reporting on financial losses and recovery only. Each TOC trains their own staff to deliver the company policy. As far as we can establish, there are limited means for any external body to hold TOCs, individually or collectively, to account for their revenue protection activities. Ticketless travel surveys appear to be one of the primary mechanisms used by DfT to hold its TOCs to account for meeting revenue protection requirements, but our understanding is that it has a relatively narrow focus.

4.106 The absence of an overarching body with scope to hold TOCs to account means there is a lack of oversight of how the whole revenue protection system collectively works. Furthermore, there is no requirement for TOCs to report on the use of their powers and be accountable for the balance of outcomes under revenue protection policy and practice.

Findings

Internal monitoring and incentives

4.107 Practices for internal reporting and monitoring differ. Twelve TOCs said they use passenger complaints data to provide feedback on staff interventions, or to provide additional training. Some TOCs also advised that they used audits into staff performance, ticketless travel surveys and revenue recovered to inform approaches to policy on revenue protection.

4.108 No TOC provided information on internal assurance processes beyond a measure of revenue recovered and ticketless travel reduction to appraise the effectiveness of the approaches in use. No TOC provided information of external assurance of revenue protection policies e.g. conducting third party reviews of the effectiveness and impact of their polices on passenger behaviour and passenger experiences.

4.109 Where TOCs use third party contractors, some TOCs demonstrated assurance and monitoring of the third-party contractors through their contracts. Our analysis of the contracts revealed significant variety in service level agreements and outcomes that TOCs specified. Contract management typically included regular reviews and meetings between the TOC and the third-party, and access to dashboards to allow for real time monitoring of performance and trends.

4.110 We did not find evidence that TOCs required revenue protection staff to meet targets or quotas for issuing penalty fares or UFNs. Savanta’s research confirmed that although some departmental targets do exist, TOCs did not offer or set individual targets for operational staff. Staff and managers both felt that such targets would be undesirable and would negatively impact on good working practices.

Data, external reporting and information sharing

4.111 There is no common industry dataset for recording and analysing revenue protection activity. TOCs can take different approaches to recording data, making it harder to meaningfully compare their activity.

4.112 Added to this, TOCs do not publish data on their revenue protection actions, and there is no overall public reporting on this either, which prevents public scrutiny. Nor do TOCs routinely share data between themselves, which constrains their ability to share best practice and to identify and resolve areas of inconsistency in how revenue protection tools are applied in practice.

4.113 There is also no overarching industry group focused on revenue protection. This is in contrast to the industry approach to tackling fraud, which is coordinated through the Rail Industry Fraud Forum. This allows TOCs and retailers to share information and best practice and to adapt approaches to the changing fraud landscape, thereby supporting a more joined up approach.

Staff training and performance

Training

4.114 All TOCs provided clear evidence of staff training requirements. Despite TOCs each having their own staff training programmes and resources, materials usually covered common themes, such as the relevant legislative and policy framework, ticketing types and passenger safeguarding (including guidance for checking tickets of passengers with disabilities, under 16s and vulnerable passengers). Some TOCs also included training on use of passenger-facing customer service skills, applying discretion in assessing potential fare evasion and how to manage conflict.

4.115 The quality and content of the training courses supplied to us by TOCs varied. There was both duplication and variation in alignment on some core activities. It was clear that TOCs mostly approached training of staff with rigour, particularly in respect of legal duties, personal safety and requirements on staff for monitoring passenger safety, including for example terrorism and safeguarding. However, it was also apparent that TOCs are missing opportunities to coordinate these activities and benefit from some standardisation and economies of scale, in addition to raising overall standards by agreeing and adopting industry-leading best practice.

4.116 Aligning training practices and materials increases the likelihood of a more consistent approach to implementing revenue protection activity and, therefore, the likelihood of passengers experiencing a consistent approach. This is particularly important given the role of staff discretion in deciding the revenue protection action taken against passengers.

4.117 A way to achieve this is for training to be accredited and a core syllabus agreed as part of establishing a common revenue protection framework. This also provides benefits of recognised qualifications for members of staff, reduces duplication in training and assessing staff and demonstrates professionalism in the revenue protection role.

Staff performance

4.118 Revenue protection staff face many challenges in their role interacting with passengers. There are a number of factors which may increase the likelihood of a difficult encounter on both sides – a closed and potentially busy environment, potential lack of passenger (and, very occasionally, staff) understanding of T&Cs and perceptions of fairness, challenges for staff in accurately gauging intent. We saw for ourselves (via site visits) that staff can face aggressive or hostile behaviour, including passengers pushing through ticket gates or refusing to stop when asked to show a ticket.

4.119 Where passengers do comply with requests by revenue protection staff, a conflict can still emerge. Most passengers we observed cooperated with staff. However, each passenger interaction is different, and we saw the value of skilled staff who can control situations and demonstrate strong influencing behaviours and people management skills when tackling challenging situations.

4.120 All TOCs provided information to show that staff performance is evaluated through line management chains. Two TOCs provided evidence of wider reviews of staff performance examining qualitative data. One included continuous assessment for competence and fitness for revenue protection officers, including reviewing the impact of human factors and behaviours when carrying out revenue protection duties.

4.121 We saw some evidence showing how TOCs evaluate the effectiveness and impact of staff when dealing with passengers for revenue protection purposes. This is mainly done through observation of interactions in performance assessments and staff reviews. We observed some TOCs who had more comprehensive and detailed arrangements for evaluating staff performance and outcomes than others. This indicates there are opportunities to share best practice and learning in this area.

4.122 During our site visits shadowing revenue protection staff, we heard staff express frustration at the lack of feedback loops and joined up decision-making in some aspects of their job roles. Some wanted more assurance that the decisions they were making on the ground were delivering the right outcomes for passengers and the business. For example, if a decision they had made to issue a penalty fare was subsequently overturned through an appeal, they said they would like to know about this so they could take this into account in future.

4.123 Similarly (and further to paragraphs 3.35 to 3.38), they felt that there could be better feedback loops between revenue protection and retail to address issues that cause passengers to make genuine mistakes or which create loopholes for fare evaders. As such, it would be beneficial to have channels through which they could give feedback on issues with existing products.

4.124 It was also suggested that there would be value in revenue protection staff being more involved in the process around the development of new ticketing products, processes and T&Cs. They felt that their experience in understanding how fare evaders might exploit new systems or how passengers can make honest mistakes was not being fully utilised and could help reduce the risk of revenue loss.

Conclusions on assurance and accountability

4.125 We found that TOCs are largely self-assessing and self-assuring revenue protection performance. There is no common approach to data collection, and any data or analysis that is held is not shared externally with the industry or published for passengers’ (or other interested parties’) scrutiny. This creates a lack of transparency which limits accountability and limits opportunities for continuous improvement in policy and process. There is also scope to optimise arrangements for training and performance of staff to support better outcomes.

4.126 Unlike other issues across the network, there is also no central industry coordination regarding revenue protection. This limits the sharing of data and best practice and inhibits the development or a more consistent approach to revenue protection. Better information and data sharing would also allow for continuous improvement of the industry approach to react to changing trends and issues in revenue protection.

Relevant recommendations (our full recommendations are in chapter 6)

- Recommendation 2 (‘Strengthen consistency in how passengers are treated when ticket issues arise’) covers matters relating to staffing.

- Recommendation 5 (‘Greater coordination, oversight and transparency of revenue protection activity’) addresses the other issues raised, including the need for better feedback loops to support continuous improvement and more joined up decision making.